Sir Humphrey : Bernard, what is the purpose of our defence policy?

Bernard Woolley : To defend Britain.

Sir Humphrey : No, Bernard. It is to make people believe Britain is defended.

Bernard Woolley : The Russians?

Sir Humphrey : Not the Russians, the British! The Russians know it's not.

Yes Prime Minister (1988)

Introduction

As part of my day job, I’ve written and co-written pretty extensively about UK defence. I’ve taken a particular interest in the broken world of Ministry of Defence (MOD) procurement.

For decades, the UK has overpaid defence primes for underpowered, bespoke systems that arrive years late and significantly over-budget. This includes £1.5 billion on drones that couldn’t fly in bad weather, £5.5 billion on armoured vehicles that injured their operators, and £3.2 billion on a battlefield communications system running half a decade behind schedule.

In my interactions with ‘stakeholders’ - whether they’re civil servants, military, or executives at defence companies - I routinely hear some version of “we’ll sort it out when there’s a war on”. The idea being that the system just needs a short, sharp shock to get its act together.

This dangerous assumption is implicit in a couple of things.

Firstly, the government’s repeated insistence that it will increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP “as soon as resources allow”. This assumes that the outside world will arrange itself to the Treasury’s timetable.

Secondly, last week, the UK government announced plans to cut five warships, a fleet of drones, and to retire dozens of its oldest Chinook helicopters early. This will save approximately £500 million over the next five years.

Some of these cuts are reasonable, including Watchkeeper (the drone programme referenced above), but others are more concerning. For example, the Chinook replacements won’t start arriving until 2027. Nor will the Navy’s new class of frigate. The decision to retire amphibious assault ships HMS Albion and HMS Bulwark had been considered by the previous government. Then Shadow, now real Defence Secretary John Healey said earlier this year that the proposals he is now enacting “would further hollow out our forces and raise serious concern over future operations for the Royal Marines”.

These decisions have been taken in the hope that we can muddle our way through until new capabilities arrive and in the event of a crisis, something will turn up.

But I believe that the idea that UK defence can ramp up quickly in an emergency is profoundly short-sighted. It involves turning a blind eye to the depleted state of our armed forces, overestimates how easy a sudden ramp-up would be, and relies on a selective reading of history.

The cupboard is bare

In September of this year, the Lords International Relations and Defence Committee published a devastating report on the state of UK defence readiness. The committee found that “the UK’s Armed Forces lack the mass, resilience, and internal coherence necessary to maintain a deterrent effect and respond effectively to prolonged and high-intensity warfare”.

They point to the UK’s inability to simultaneously deploy fighting forces, while guarding long lines of communication and protecting critical national infrastructure. This stems from our forces’ size and structure being “predicated on the belief that conflicts would be resolved within weeks, rather than years”.

The report concludes that “governments, have so far, lacked an honest narrative about Defence’s ambitions, resources, threats and risk”.

You see this everywhere.

The armed forces have shrunk by nearly 30% since 2000.

Even recent shows of strength, such as our strikes on Houthi targets in Yemen earlier this year, highlight underlying weaknesses.

The UK’s contribution was largely symbolic, four Eurofighter Typhoons striking two targets. Delivery of the second and third squadron of F-35B Joint Strike fighters has been delayed. HMS Diamond, the Type 45 destroyer currently protecting shipping in the Red Sea currently can’t attack land targets. No submarines were available, due to the delays in operationalising the new Astute-class submarines. In fact, Britain’s current submarine fleet is barely large enough to protect the nuclear deterrent.

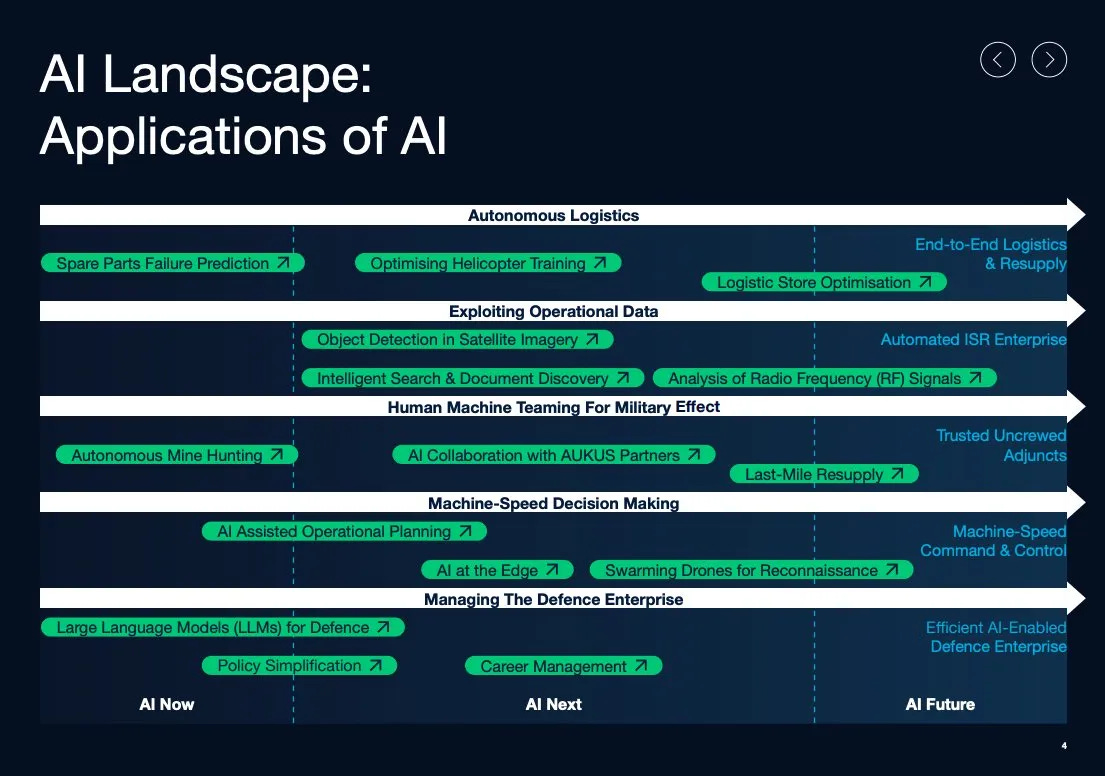

Despite drone warfare gaining in salience, the UK is a laggard. The Watchkeeper programme was a shambles, while the ‘Defence Drone Strategy’ published earlier this year was primarily a set of pictures, case studies, and aspirations to partner with industry. It was revealed earlier this year that the UK’s drone trial squadron had not conducted any trials since being formed in 2020 due to a lack of drones.

Meanwhile, the Defence Artificial Intelligence Strategy seemingly envisages the UK prioritising the use of AI for career management over enabling swarms of drones.

At the end of last year, the National Audit Office concluded the MOD’s Equipment Plan for the next ten years has a £16.9 billion black hole centre, while the MOD can’t keep track of the equipment it does have.

The rot runs deep

It would be easy to attribute the poor state of critical institutions to an extended period of austerity following the 2008 global financial crisis. There’s definitely some truth in this - but it’s incomplete as an explanation.

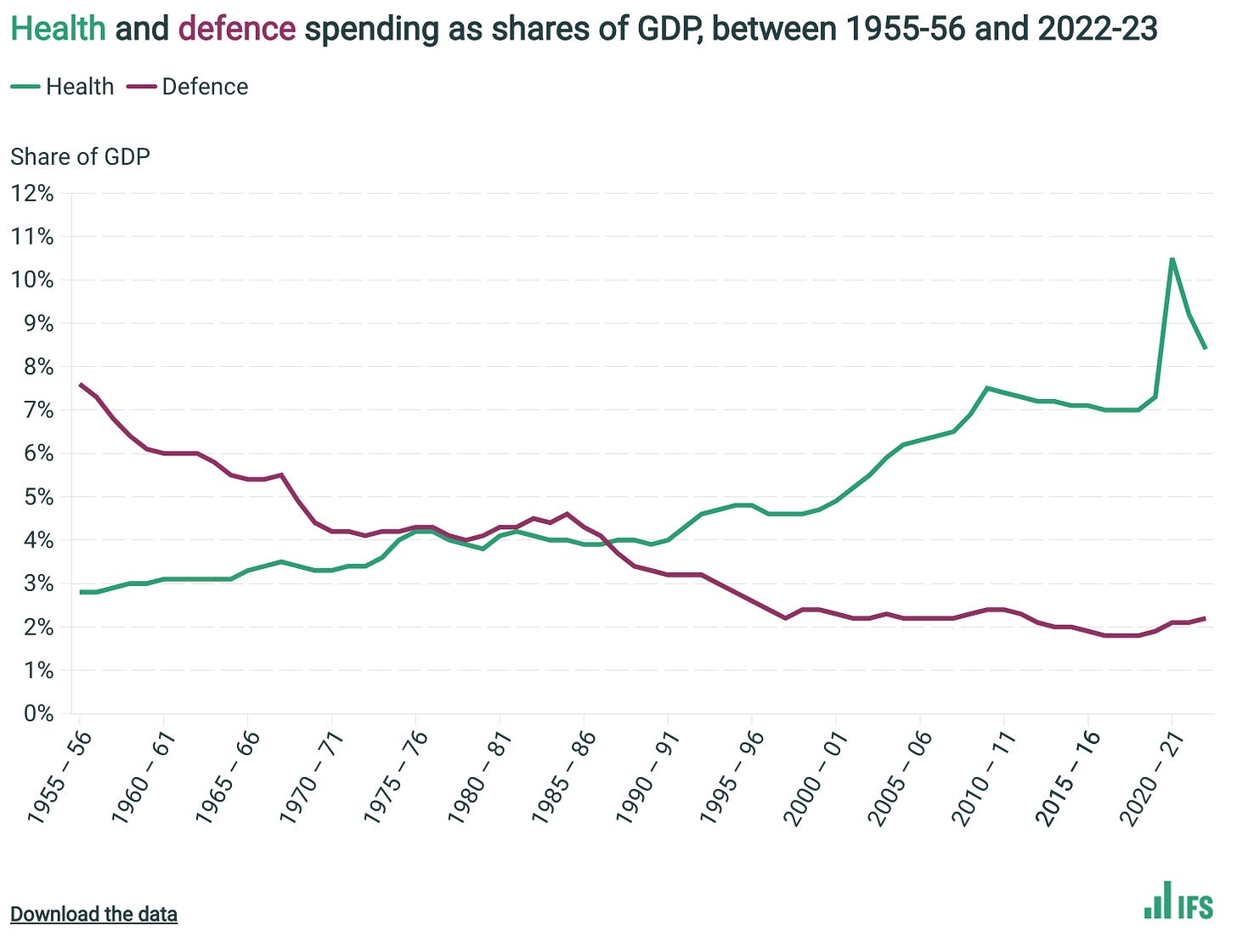

We’re witnessing the consequences of a 30-year trend of borrowing from defence to pay for the rest of the public realm.

This trend started in the 1990s after the Cold War, but the UK didn’t update its approach as the War on Terror broke out.

You’d be forgiven for assuming that the era of deep UK-US cooperation with simultaneous major deployments would be a golden age for UK defence spending.

But the mid-2000s were counterintuitively an era of retrenchment for UK defence.

Much of the cost of the Iraq and Afghanistan deployments was met via a special Treasury contingency rather than through the core MOD budget, which was squeezed. In this era, ministers could confidently state that defence receiving real-terms spending increases. But these were often a sliver above low inflation rates and did little to reduce pressure on resources. Even as British forces were deployed overseas, they were the target of penny-pinching.

In December 2003, the government published a defence white paper. It proposed a move away from heavy-weight land forces, and outlined reductions in equipment and manpower. This was followed by a sequel in July 2004 that spelt out the specifics, including a 10,000 fewer personnel across the three services, reductions in numbers of helicopters, missile launchers, nuclear attack submarines, patrol vessels, and frigates.

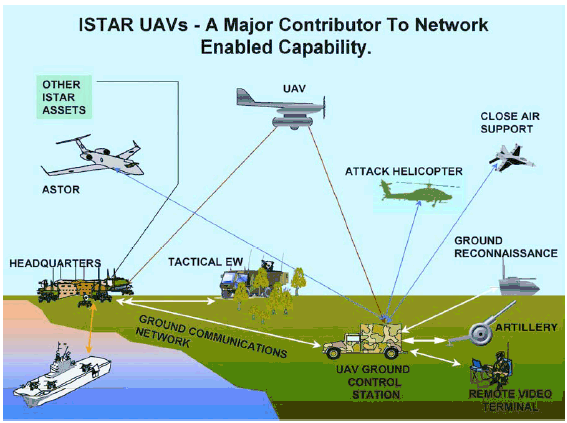

These reductions would be offset by the embrace of “network-enabled capability” where, thanks to technology, we would be “able to exploit effects-based planning operations, using forces which are truly adaptable, capable of even greater levels of precision and rapidly deployable”. In essence, shortening time for decision makers and between shooters and sensors.

This would in turn support “effects-based operations” - military activities designed to create specific psychological, physical, or behavioural outcomes, rather than simply destroying targets. The MOD stopped short of defining what this meant specifically in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Hindsight may be 20:20, but there were plenty of voices expressing alarm about this approach at the time.

In June 2004, the House of Commons Defence Committee published a highly critical report on the 2003 white paper.

It warned that the MOD was abusing the language of doctrine, stating that: “The suspicion has grown that the focus on agility, effect without mass and the move away from a platform focus has less to do with an intellectually coherent strategy of effects-based warfare than with the need to ‘cut our cloth’ as best we can”. Elsewhere the report called on the MOD to “urgently” tackle ‘gapping’ - the practice of leaving non-essential posts vacant to tackle manpower shortages.

As with the current government, capabilities were scrapped, new ones were promised, but without budgets or timelines for procurement.

At the time, Michael Codner, a senior defence analyst at RUSI noted that the plan was “published at a time when there was widespread awareness that there was not enough money in the Defence Budget to fund defence activities and the equipment plan and the imbalance was too large to be addressed by modest increases in defence spending and greater efficiencies”.

There was good reason to be concerned.

Since 1998, the UK had planned on the basis that while its armed forces could be engaged in two substantial deployments simultaneously, these could not run concurrently for more than six months. They also did not expect both deployments to “involve warfighting”.

By 2004, the UK had comprehensively blown through these assumptions.

While the US and UK governments were publicly maintaining the pretence that Iraqi self-governance was just around the corner, this was beginning to collide with reality. By the time of the 2004 capabilities paper, attacks by insurgents were already gaining in sophistication, Muqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi Army uprising was under way, and we’d seen the First Battle of Fallujah. Drawdowns weren’t imminent.

Before we’d exceeded these assumptions, the UK’s armed forces were already stretched. The official Iraq Inquiry spells out the state of pre-invasion preparation in black and white.

The report concludes that “after the invasion began, it became clear that some personnel had not been equipped with desert clothing and body armour … and there were shortages of ammunition”. As well as actual shortages - poor asset tracking made it hard to get equipment to the right people. This deficiency had been identified during the 1991 Gulf War, but the MOD had not remedied it 12 years later.

Sir John Reith, former Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe within NATO described the equipment policy as “just enough just in time” - and said that it didn’t work.

During the long counter-insurgency phase of the operation, one vehicle came to symbolise the deficiencies of the UK’s approach: the Snatch Land Rover.

These lightly armoured patrol vehicles had been designed for use in Northern Ireland to protect against small arms fire and basic explosive devices during the Troubles. They were inappropriate against larger IEDs and rocket propelled grenades, but as General Sir Mike Jackson, Chief of the Defence Staff from 2003 to 2006 told the inquiry:

“Snatch Land Rovers were deployed to Iraq because they were available or could be made available as we drew down from Northern Ireland, and without them, it would have been completely soft-skinned Land Rovers. That’s where the state of the equipment inventory was at that point”.

37 British personnel died in these vehicles in Afghanistan and Iraq, leading them to be dubbed ‘mobile coffins’.

Anyone who followed the news regularly in the UK from about 2006 and 2010 will remember the widely criticised shortage of Chinook helicopters in Afghanistan.

2006 marked the deployment of British forces to Helmand Province to shore up the Afghan authorities, who were struggling against a resurgent Taliban.

While the military’s senior leadership assured the government that a 3,000-strong British task force could get the job done, UK forces were undermanned and underequipped. Theo Farrell’s scathing account of the war, Unwinnable quotes the reactions of members of the 16 Air Assault Brigade, after they were informed that the taskforce could not exceed 3,150. Experienced officers warned the mission would be a disaster, and identified “significant shortfalls in core equipment areas such as helicopters” . But in response, “the consistent line was that we had to make do”, as multiple requests for additional equipment were denied.

The deteriorating relationship between the Chancellor and the Prime Minister meant the Treasury refused to make more resources available, and there was little pushback at the most senior military level.

Both the military and political factions appeared unbothered by the several years-long overstretch of their own planning assumptions. It’s not for nothing that Farell concludes that: “‘Ultimately, the British campaign in Helmand was characterised by political absenteeism and military hubris’.

The Iraq Inquiry also flagged up a similar failing among military leaders, finding that a “can do” attitude in the armed forces led to “over-optimistic assessments” at the expense of “accurate and frank reporting”.

To summarise, even when UK defence spending was higher, the UK was unable to adequately resource military activity that it had planned in advance. The notion, with the armoury empty, that it would be able to resource unplanned activity seems Pollyannaish in the extreme.

Things can only get worse

When the 2010 Conservative-Lib Dem Coalition came to power and embarked on a course of austerity, Sir Rodric Braithwaite, former chairman of the Joint Intelligence Committee was scathing about their inheritance, saying:

“The new Coalition government came to power to find that their predecessors had bequeathed them a national defence strategy that was intellectually void; a military procurement policy paid for on the Micawber principle - that something would surely turn up, but measured in billions rather than sixpences; a bunch of generals on the verge of revolt; a vision of Britain’s place and influence in the world based largely on wishful thinking; and a horrendous financial crisis.”

The 2010 Strategic Defence Review introduced significant cuts in personnel across the services, a 40% reduction in Britain’s fleet of Challenger 2 tanks, the culling of the Navy’s fleet of Harrier jump jets, the decommissioning of 9 frigates and destroyers, the mothballing of aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal, and the scraping of the Nimrod maritime patrol aircraft shortly before its completion.

This stripping of the armoury created operational problems in the coming years.

For example, the Harrier was the UK’s only fixed-wing aircraft capable of operating from a carrier. Its early retirement left the Royal Navy without this capability for over a decade until the F-35B Lighting II became operational. This meant that during the UK’s operations in Libya, the UK had to pick the more expensive and less flexible option of operating from Italy, rather than from a nearby carrier.

Scrapping the Nimrod left the UK without a maritime patrol aircraft - a useful capability for a geopolitically significant island nation. The Nimrod replacement, the P-8 Poseidon, wasn’t delivered until 2019. In the meantime, UK personnel had to be loaned to allied nations to maintain their skills. This left the UK reliant on US aircraft and a diminished frigate fleet to spot and counter Russian submarine incursions - which analysts warned about at the time. Over the course of the decade, Russian incursions to map out undersea cables increased.

Plucky British improvisation?

Part of our national mythos is this idea that Britain can always pull it together once its back is against the wall. Ingenuity, improvisation, and spirit will lead us to triumph against the odds.

Let’s break the first rule of arguing on the Internet and look at World War II.

The opening phases of the war, with defeat in Norway through to the fall of France in June 1940 were not Britain’s finest hour. Interwar intellectual stagnation in the military and an army constructed on the basis of what politicians believed the country would tolerate paying for was disastrous. There was a shortage of tanks, defence planners seemed uninterested in them, and little consideration had been given to the style of land-air operations that the Germans would use to devastating effect.1

But despite this early military incompetence - the UK industrial-base remained resilient. So much so, that Churchill later admitted to being overly pessimistic about the state of the country in his memoirs. By the outbreak of war, Britain was both self-sufficient in energy and the world’s biggest exporter of coal. It was also the world’s biggest exporter of arms. Between 1935 and 1939, arms expenditure increased at a faster rate than it did during the pre-World War I arms race. During the interwar years, the Royal Navy out-built every other navy in the world in almost every class of warship. 2

In short, it’s easier to compensate for doctrinal screw-up when the arsenal isn’t empty and you’re capable of replenishing at least some of it.

If we want to continue on the historic detour, Britain in part prevailed in the Napoleonic Wars of the nineteenth century thanks to the significant investment in its naval capacity in the 1780s and 90s. Instead of cutting spending following the American Revolutionary War of 1783, as was normal in the eighteenth century, William Pitt’s government increased it. The number of men at dockyards was maintained at wartime levels. Between 1783 and 1793 alone, 138 ships of the line were built or given major repairs. This was done while paying down the national debt.3

When you’re working a smaller defence-industrial base, as the UK is now, that’s been starved of orders for a long time, you can’t just flick a switch and fire up production.

Producing weapons or ammunition requires staff, materials, equipment, and infrastructure. As European governments ramped up orders following the Ukraine invasion, they found 10-20 month waits for unguided shells, rising to 36 for guided ones. With concerns that the UK would exhaust its stocks of ammunition in 8-10 days in the event of intense warfighting, this isn’t ideal.

Rheinmetall, the German arms giant, is on a buying spree to help it meet orders. In August alone, it acquired a South African engineering firm and an American vehicle manufacturer. One month earlier, a new factory in Hungary was completed. In February, it acquired a majority stake in a Romanian vehicle manufacturer.

Parallel efforts are not happening on a similar scale in the UK. This isn’t because Rheinmetall is particularly smart or patriotic, while their British competitors are stupid. It’s because UK-based manufacturers do not believe that they will receive the orders necessary to justify this kind of outlay.

When disaster strikes

It’s of course impossible to know exactly how British defence would respond in the event of an emergency, But there have been recent incidents where crumbling arms of the state have been tested. And they performed dismally.

The recent Coronavirus pandemic was handled poorly in many countries, but the UK experienced one of the worst death tolls of large European economies. Save for the intervention of a few talented outsiders, it could have been worse.

While the official inquiry into the pandemic is still going on, Module One, focused on pandemic preparedness, has been published. They found that despite “reams of documentation” and a “labyrinthine” institutional setup, the UK’s pandemic preparedness was damaged by bureaucracy, groupthink, outdated assumptions, and a lack of interest or challenge from ministers. Sound familiar?

The authors had “no hesitation in concluding that the processes, planning and policy of the civil contingency structures within the UK government and devolved administrations and civil services failed their citizens”.

The UK’s Vaccine Taskforce (VTF) was one of the few bright spots of an otherwise shambolic pandemic response.

Chaired by venture capitalist Kate Bingham, the VTF was tasked with rapidly sourcing and deploying a Covid vaccine. It operated with a high degree of autonomy and made quick decisions on procurement and investment, backing multiple different vaccine candidates before it knew which would succeed. This meant that the UK became one of the first countries to begin mass vaccination and achieved high vaccination rates relatively quickly.

But the bureaucracy was seemingly determined to kill off this agile, risk-tolerant body from day one.

The frustration is palpable in the pages of The Long Shot, Kate Bingham’s book about the experience. She describes her team having to waste time filling in hundreds of pages of Whitehall business case documentation:

The standard Whitehall case required us to quantify the benefits to the UK economy based on the extent to which vaccines put a stop to the pandemic - also impossible to determine in June 2020. [...] We needed to produce estimates of where the economy would be without a vaccine and how much larger it might be following vaccination, but without yet knowing how effective the vaccine was at saving the lives of different age groups, or who would be vaccinated and when. A graph was inserted for the sake of form.

Within two months of the taskforce being launched, the National Audit Office began investigating the VTF to ensure it used “their resources efficiently, effectively and with economy”, jamming up its work with requests for information and meetings. Meanwhile, Kate Bingham herself was the target of vicious partisan attacks in the media.

In short, the UK’s bureaucratic and political class were keen to kill off the most successful part of our response. We’re very lucky they didn’t succeed.

But Ukraine?

As Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine in February 2022, most observers expected that Putin would quickly achieve his war aims. Famously, the US offered to airlift President Zelensky to safety. The Ukrainians’ early and ongoing success in holding out against a numerically superior military has rightly been attributed to the ingenious use of asymmetric tactics, supported by the total mobilisation of society in support of the war effort.

One of the most visible manifestations was the explosion of teams working on drones. These efforts have now evolved into a highly capable industry that’s respected internationally. Can we take hope from this?

Yes and no.

While there is much we can learn from the admirable speed and efficiency with which the Ukrainians now procure technology, societal mobilisation carries fewer transferable lessons.

I don’t want to stare into the crystal ball too much, but I think the chances of Russian tanks rolling past Watford Gap service station are slim.

In the event of an incursion into Finland, an attack on one of the Baltic States, or an escalation in Moldova - the average British citizen will not be fighting for their survival. I doubt there will be the political will to mobilise all of society in response. In reality, the UK is on course to be a junior partner in a multinational coalition.

I sometimes hear that the UK’s strength is its technology or special forces. These are more valuable than mass. This may well be true, even if there’s scant evidence of the former in defence. But when a country like Estonia, Poland, or Finland is putting a meaningful proportion of its adult population on the line, while the UK can’t deploy equipment or people at scale, can we reasonably expect to have an equal seat at the table?

In the worst case scenario, a future conflict with Russia could overlap with a confrontation in the South China Sea. A recent RUSI report noted that in the event of a crisis in the Taiwan Strait, European nations risked facing critical gaps in missile defence and anti-submarine warfare. It’ll be all hands to the pump.

The isolationist will say that this doesn’t matter. What happens in Chișinău doesn’t matter in Crewe. But this is where sangfroid can tip over into being sans brain.

Even if we put morality aside, a Russian-dominated or conflict-ridden Central and Eastern Europe would be dire for UK interests. Bilateral trade with Poland alone is worth £30 billion a year. Major UK companies have significant market presences in these countries, while Eastern Europe is deeply integrated into UK manufacturing supply chains for automotive parts, electrical components, and agriculture products.

Forfeiting our seat at the table leaves the UK dependent on others for the defence of critical national interests.

Whither Britannia?

Preparing for war in the same way we prepared for the pandemic isn’t an option.

So where does this leave us?

For a start, urgent increases in defence spending are needed. We should be moving towards 3% of GDP urgently at a minimum.

As we move to restock the armoury, important questions need to be asked about the exact role the government sees the UK playing in any future conflict. Historically, the MOD has ducked these questions, leaving us with ‘a shopfront military’, in the words of one former senior official. It means we’ve spent close to £7 billion building two aircraft carriers to project force, while draining the resources needed for the accompanying planes and escorts.

Do we envisage a world in which the UK plays a meaningful role in the defence of our European allies, while we send a carrier group to the South China Sea as part of an ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’? Or should we scale back our focus to Europe and the Mediterranean?

There are some things that we definitely need to do. For a start, greater mass is essential. The vision of the UK as some kind of elite defence R&D island is appealing, but fanciful.

Whatever we choose to do, our armed forces will need to be larger and we will have to pay for them.

But there are real questions and trade-offs about the extent to which we balance older-school mass with new technology. While the drone has become the defining image of the war in Ukraine, much of the conflict still resembles an early twentieth century clash of mass armies.

We also need to have an honest conversation with both ourselves and our US and European allies about the role we will and won’t play in any future confrontations with our adversaries. The official acceptance that we are a second-tier military power will be bad for our image, but significantly better for our ability to plan.

But wherever we land on these questions, business as usual with more money is not going to be the answer. The MOD’s current procurement system, for example, is beyond repair. While I’m usually sceptical of new units or agents, there’s a strong case for moving defence acquisition out of a captured MOD bureaucracy.

We could bring outsiders in to operate it, exempted from civil service payscales and run competitive trials for solutions as opposed to a paper requirements process. This would also free the process from the MOD’s fixation on bespoke solutions. Rather than overpaying contractors to format a special GB drone, we might just buy the one that works quickly and in bulk.

By commissioning a Strategic Defence Review led by credible, independent outsiders, the new government has given itself the space to begin having these difficult discussions. In October, the government created a new National Armaments Director to drive procurement reform. An accountable individual is welcome, but it remains to be seen if they’ll have the powers they need to bring about change.

We can only hope so.

More MOD ‘strategies’ that make vague allusions to Britain’s place in a changing world won’t cut it.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer (Air Street Capital), any current or former UK Government officials, or anyone I’ve spoken to who’s served in the armed forces. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Photo credits:

Canal Hotel Bombing: MSGT JAMES M. BOWMAN, USAF, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales meet at sea for the first time. Petty Officer Photographer Jay Allen, OGL 3, via Wikimedia Commons.

For a history of how Britain went from pioneering an early version of Blitzkrieg at the end of World War I before unlearning all the lessons, check out Richard Dannatt and Robert Lyman’s Victory to Defeat: the British Army, 1918-1940. I enjoyed it, even if the political subtext was occasionally grating.

These statistics come from ch. 2 of David Edgerton’s Britain’s War Machine: Weapons Resources, and Experts in the Second World War. I don’t agree with all the book’s conclusions, but it’s a pretty good counter to the intellectually lazy assumption that the British mainland simply lived off the proceeds of the Empire.

These stats come from ch. 2 of Roger Knight’s Britain Against Napoleon

This is excellent but so much of it made me want to tear off my eyelids with my own teeth

Minor point on your mention of Hermes 450 drones not being able to fly in bad weather: relatively few drones, wherever they're made and whoever they're made for, are performant in bad weather. The reason this has not been so much of an issue in the 25 years since the first combat drones were rolled out post-9/11 is because the vast majority of combat drones are active in the Middle East. While there are obviously cloudy and rainy days in that part of the world, generally speaking it's more sunny, more of the time. Any drone war waged on UK soil would be regularly stymied by our climate.

Obviously we've seen drones being used lots in Ukraine over the last couple of years. But weather conditions are less material to the performance of kamikaze or improvised drones, which fly lower to the ground and are not designed for long-duration surveillance. There are multiple examples of Russian drone activity being much reduced in periods of inclement weather: https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-ato/3936366-enemy-reduces-drone-usage-on-southern-front-due-to-bad-weather-ukrainian-military.html