Introduction

The UK is proud of its tech ecosystem. You’ll often hear its champions boast about the quality of our universities and R&D base, or the presence of tech companies like Google DeepMind in King’s Cross. But if you spend enough time talking to civil servants and venture capitalists, you’ll also hear two acronyms: EIS and VCT.

EIS (the Enterprise Investment Scheme) and VCT (Venture Capital Trusts) were created by the UK government in 1994 and 1995 respectively and have been renewed ever since. These schemes were designed to incentivise wealthy individuals to invest in start-ups at a time when early-stage capital was scarce in the UK. By giving investors generous tax relief and downside protection, this was meant to de-risk investment in otherwise high-risk enterprises.

While the schemes have chopped and changed, the basic idea has stayed the same.

For EIS, investors can claim up to 30% of their investment (up to the value of £1M, or £2M if at least £1M is invested in “knowledge-intensive companies”) in qualifying businesses as income tax relief either in the current or previous tax year. They also receive a capital gains exemption when they sell their investment provided they’ve held it for at least three years, and loss relief against income tax. Shares bought via EIS are also inheritance tax exempt.1

VCT investors buy into the public offering of a listed company that holds shares in unlisted companies or AIM stocks. They offer a similar deal on income tax to EIS (albeit with a £200k ceiling) and with a five year year holding period. No capital gains tax is levelled on dividends.

One of the new government’s first acts in office was to extend these schemes to 2035. In a given year, around £2B is raised via EIS and around £1B through VCT.

So… great news for founders?

Unfortunately, EIS and VCT are a case study in the danger of tax breaks and subsidies. Tax relief that was once meant to act as a derisking sweetener has become the primary purpose of these schemes, with significant distorting effects. They also show us the peril of governments outsourcing the monitoring of policy to ‘stakeholders’ and how, if something is dressed up as ‘supporting business’, it’s possible to get away with murder.

High fees, poor performance

I’m going to start with one caveat. While some individuals choose to make EIS investments, many choose to invest in EIS funds. Essentially, you put your money in and over the course of (usually) a tax year, it’s invested in a portfolio of EIS-qualifying companies.

This works well for many EIS investors, who don’t want source deals or manage investments in individual companies. These funds, rather than individual investments, are going to be my focus here, although I will also briefly touch on angel syndicates - where groups of EIS-eligible investors come together to pool their resources.

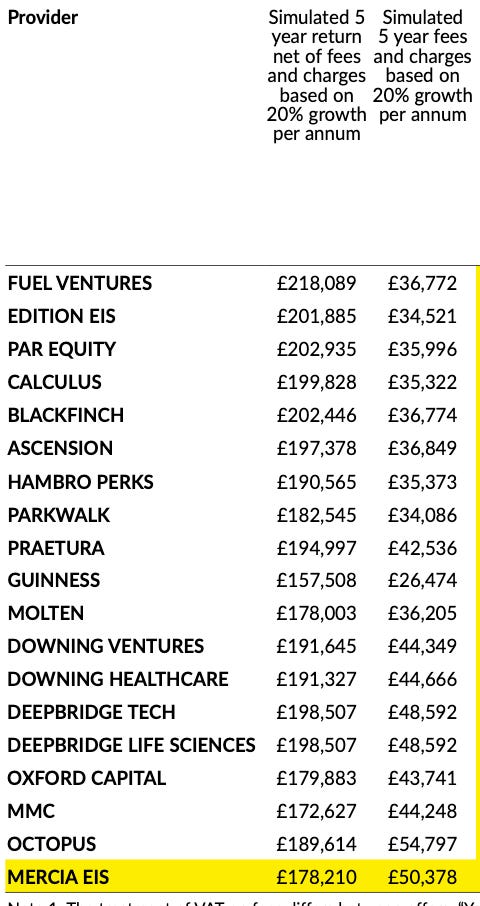

If we want to assess how well a scheme is working, the performance of the biggest investors in EIS-qualifying companies is a good starting point. EIS is a notoriously untransparent industry, but the Tax Efficient Review (says it all) produces performance breakdowns, which some funds use in their marketing. I’ve lifted this table from Mercia’s 2023 materials.

EIS funds tend to launch a new fund every year, so these stats aren’t year-on-year rises and falls. Each number reflects a different fund vintage and how the investments made in that specific tax year have fared.

These figures are … underwhelming. Risky, illiquid investments are meant to be rewarded with outsized returns. But more importantly, these numbers don’t account for fees, which are meaningfully higher than in standard VC.

In addition to the typical 2% management fee and 20% carried interest, EIS layers in a world of other charges. These include an initial charge for ‘setting up the portfolio’ (up to 5-6%) and an annual administration fee (0.2-0.5%). Most funds have a hurdle rate (a minimum level of performance above 1x before the performance fee is deducted), but there are several exceptions. Mercia, for example, doesn't have one.

There are also the fees on investee companies - which we’ll get to in a little bit…

These fees begin to stack up. The TER folk have simulated fees on a portfolio of £100k invested for five years, assuming 20% annual growth on all investee companies, no write-offs, and with all companies sold together after five years. This, of course, is a highly unrealistic scenario, but it reveals how quickly the fees stack up.

Considering the performance of many of these funds, it’s possible that the performance fee could go down, but the cost per pound of profit increases, due to the application of fixed annual fees and VAT.

This means you need to adjust all of the numbers in the nice colourful table down significantly.

To be as generous as possible, we’ll pick the best-performing recent year in the table - 2019/20. Assuming standard EIS fees but without applying the income tax relief - for investors at the time this table was compiled in 2023 - a fund needed to make 1.2x to break even. For the the annual return to cross 5%, it needed to clear 1.3x

If we look at a benchmark for non-US PE and VC firms from 2023, convert the EIS funds’ gross multiples to annualised returns net of fees, 4 of the 18 funds clear the bar, while the rest underperform, significantly for the most part. (I accept that trying to convert EIS returns like this is pretty crude, due to differences in reporting, but it’s the best I can do with the available data.)

Are the poor returns just a product of EIS?

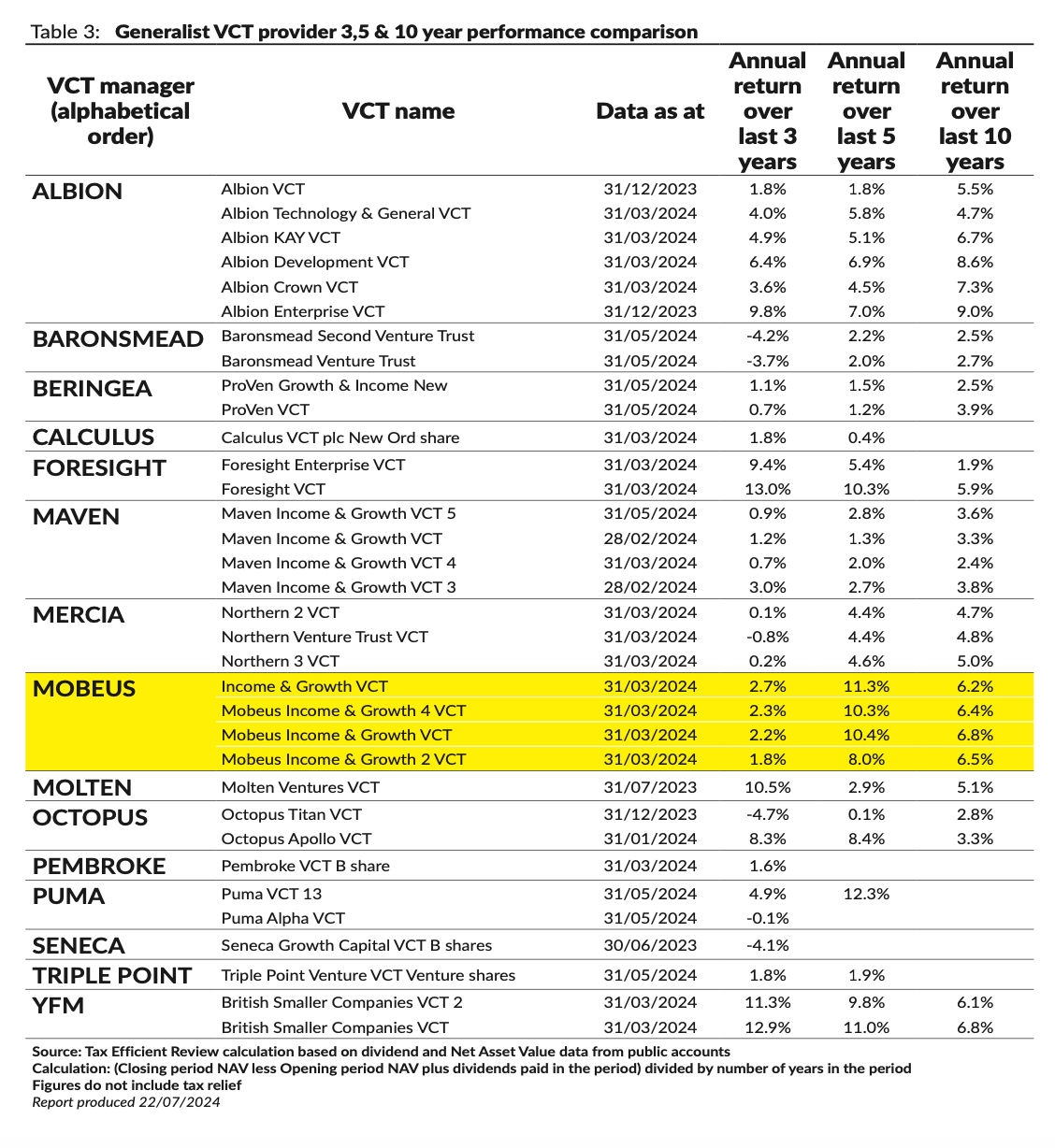

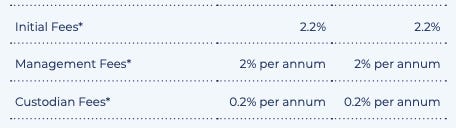

VCT fees tend to come in a percentage point or two lower, but so do the returns. (Ignore the highlights, this table is from Mobeus’ marketing materials.)

Tax relief isn’t derisking these investments, it’s keeping them alive.

Bad incentives = bad outcomes

If you accept that the purpose of EIS is really to act as tax relief and you ignore most fund managers’ rhetoric around innovation, the lacklustre performance makes a lot more sense. And to be fair to managers, it’s pretty transparent.

You see it in the advertising:

Or in the other services they provide:

If you’re an investment manager in the tax efficiency game, you have two primary incentives: (i) to get as much investors’ money out of the door as possible during a tax year, (ii) to protect your downside.

In short, it’s a perfect mechanism for allocating capital inefficiently.

For most EIS/VCT funds, this manifests in poor company selection or a bias towards doubling down on their existing portfolio, regardless of growth prospects. In fact, one founder I spoke to told me that their rejection from an EIS fund explicitly said that the technology they were building was “high risk, high reward”, so it was incompatible with the fund’s thesis.

This rejection makes no sense in venture. If what you’re selling is 30% income tax relief, of course you’d rather choose companies that reliably provide a 1-1.5x return, so you can just give people their money back later.

You can see this when you go into the nitty-gritty of their year-on-year investments. Unfortunately, I don’t have an army of research assistants, so I’m going off the limited number of freely available TER fund breakdowns I could access.

The first product I looked at was Mercia EIS Fund and Knowledge-Intensive EIS Fund.

I noticed a few companies that were ‘complete write-offs’ despite the fund having doubled down on them year after year. Sometimes a business seems promising and doesn’t work out. But what I found striking was that even at the time, many of these companies were displaying limited signs of life.

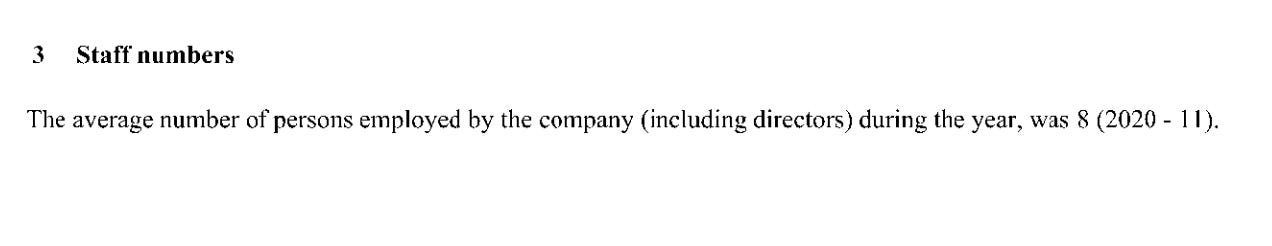

For example, over four vintages they invested in a company called Rinicare, which offered technology for remote patient monitoring.

Far from being a young, innovative company, Rinicare had existed for 17 years before Mercia made their first investment in 2019. In that time, it had failed to grow or achieve any meaningful commercial traction. It largely appeared to live off government grants. Within a year of investing, the team had shrunk from 12 to 11, and Mercia doubled down again after it declined to 8.2

The business hired back a couple of people the next year, but it’s hard to look at a team struggling to stay in double digits and significant losses 17-19 years in, and understand what the Mercia team saw in the business.

Rincare isn’t an isolated example, Manchester Imaging and Pertinax Pharma are two university spinouts Mercia repeatedly invested in before a complete write-down. If you follow the journey through their accounts, you again see more and more money going in, even as growth (by basically any metric) remains elusive.

You don’t just see evidence of zombie-fication in the write-downs.

If we look at the Guinness EIS Fund,3 you can see plenty of examples of seemingly random companies that have received money repeatedly, despite limited growth in valuation. This might be because the fund is marketed as engaging in “risk mitigation” despite the fact that the government explicitly says EIS is designed to support “high risk” companies. It also explains their focus on leisure, food, and retail businesses. All noble sectors, but worthy beneficiaries of tax breaks for high-risk companies?

It’s an open secret in London that if you’re struggling to raise money from conventional VC funds, you approach EIS funds in February. Their keenness to invest leftover cash means the due diligence will usually be flimsy. Towards the end of the tax year, many will also solicit their existing portfolio, asking if they’d like to take more money (whether they need it or not). A friend of mine spoke to a manager at one of the funds in the returns table in March last year. My friend asked how they were doing and the manager replied that they were super-busy “getting money out the door”.

Free money for founders, what’s not to like? A few things.

Firstly, zombie companies are bad.

A lot of start-ups fail, and they should be allowed to. That’s how talent and ideas are recycled back into an ecosystem. Politicians repeat the myth that small businesses are the backbone of the economy, but they’re usually less productive and spend less on R&D. Incentivising the creation of new small businesses that don’t scale isn’t good in and of itself.

Secondly, if you’re a founder focused on building a killer business, a partner focused on downside protection doesn’t have the same incentives as you. Their instinct will be to push you to market before you’re ready, steer you away from ambitious R&D, stuff cash into your business and dilute you on their timelines, or to replace you at the first sign of difficulty.

Downside protection also includes a bunch of other annoying dynamics.

A founder I spoke to who received their pre-seed funding from an angel syndicate told me that as soon as the three year EIS holding period expired, he was besieged by investors demanding that he open up secondary share sales. Because of the vagaries of their tax management, these investors preferred to cash out quickly, rather than stick around and see the value of their investment increase 8x in an upcoming funding round.

If you look at the Guinness table, you see clear evidence of tranche funding - common in EIS world. Regarded as bad practice in VC much of the time, dicing up money into tranches adds operational complexity, decreases founder leverage, and creates misaligned incentives. Depending on the exact details, it can create a world where founders have to focus on ‘milestone theatre’ - where resources are diverted into short-term ‘wins’ at the expense of the long-term plan.

VCTs come with all of the problems above and more. Alongside the tax breaks, VCT investors are driven by dividends. These dividends have to come from somewhere - either portfolio companies being encouraged to burn through their cash to pay them out or via a sale. Again, it’s not hard to see the mismatch between the fund’s short-term incentives and a founder’s long-term ambitions.

Money with menaces

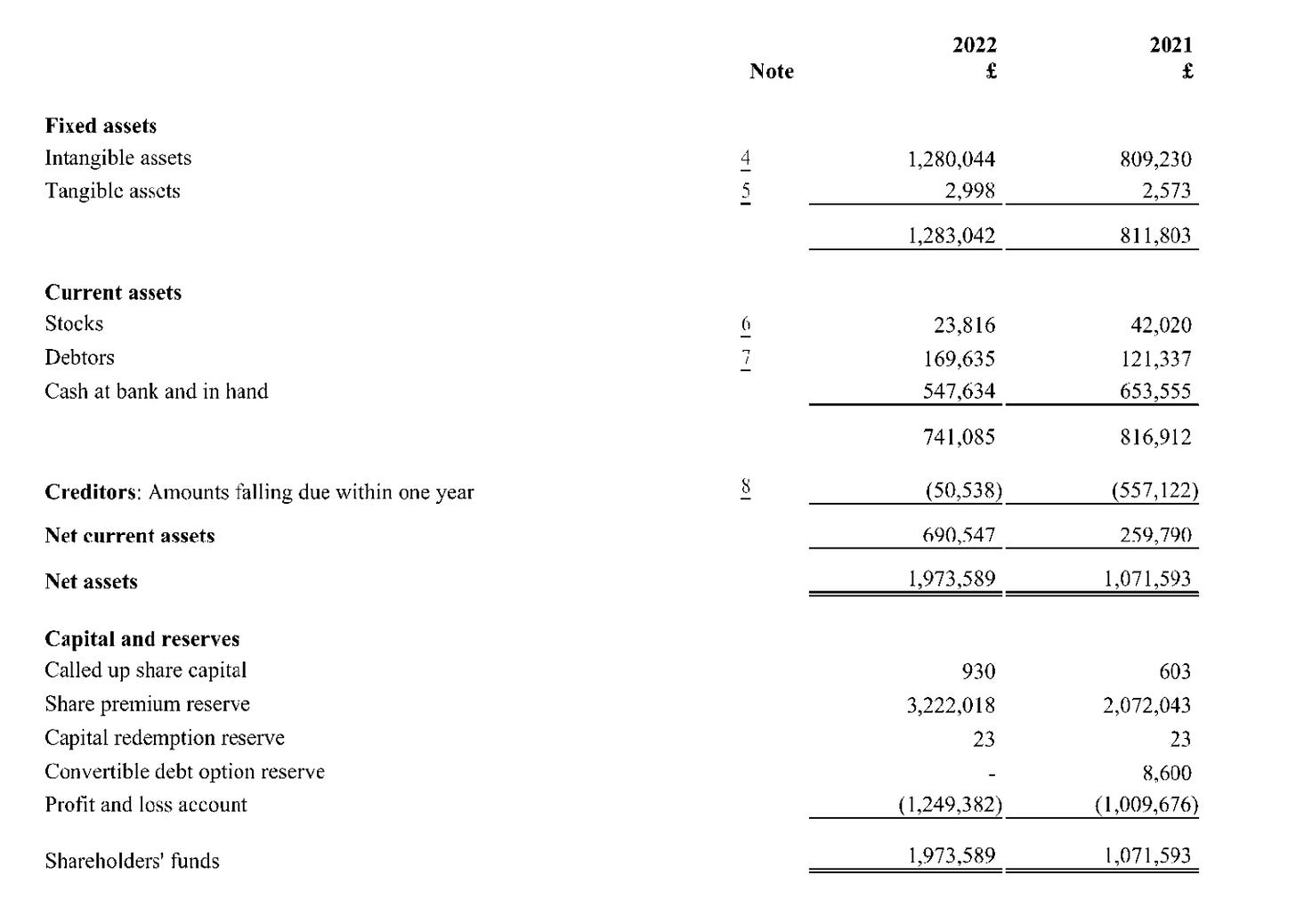

My little tour through company accounts didn’t just raise questions about EIS fund due diligence procedures, it flagged up another unedifying element of the industry: the fees.

EIS fund managers are partly compensated on the basis of fund performance, but the funds often … don’t perform that well. This means the money has to come from somewhere else: the portfolio. Not only do EIS investees have to hand over equity in exchange for investment, they also have to part with cash.

There are some funds who, to their credit, don’t do this (shout out to Molten, MMC, and Octopus), but some of the terms on offer, elsewhere, seem distinctly founder unfriendly. In some cases, funds split fees evenly between investees and investors.

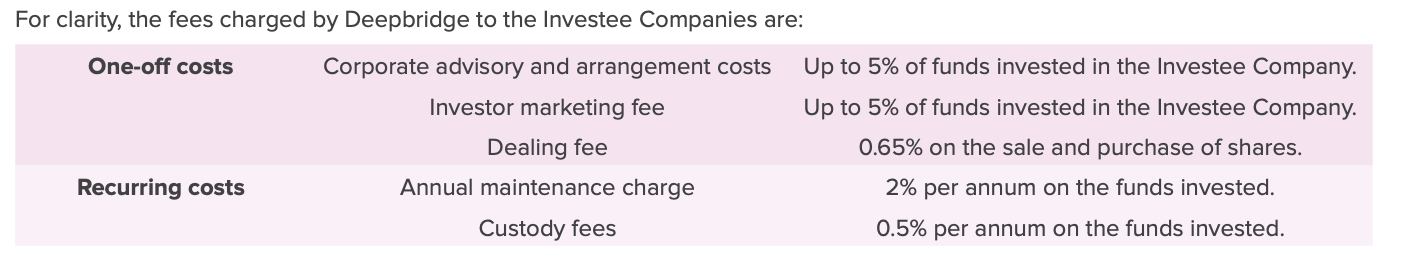

For example, Deepbridge advertises that investors don’t pay fees on subscription. Instead, founders pay.

Deepbridge isn’t alone. For example, over at Guinness Ventures, founders get these terms.

The picture isn’t much better in the VCT world.

If you tried to offer these terms in the Valley, you would be met with a mixture of astonishment, derision, and fury.

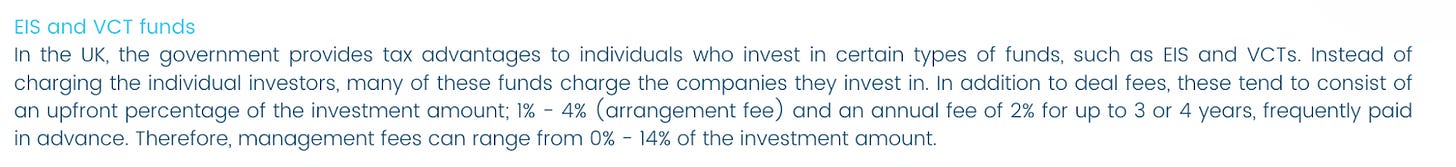

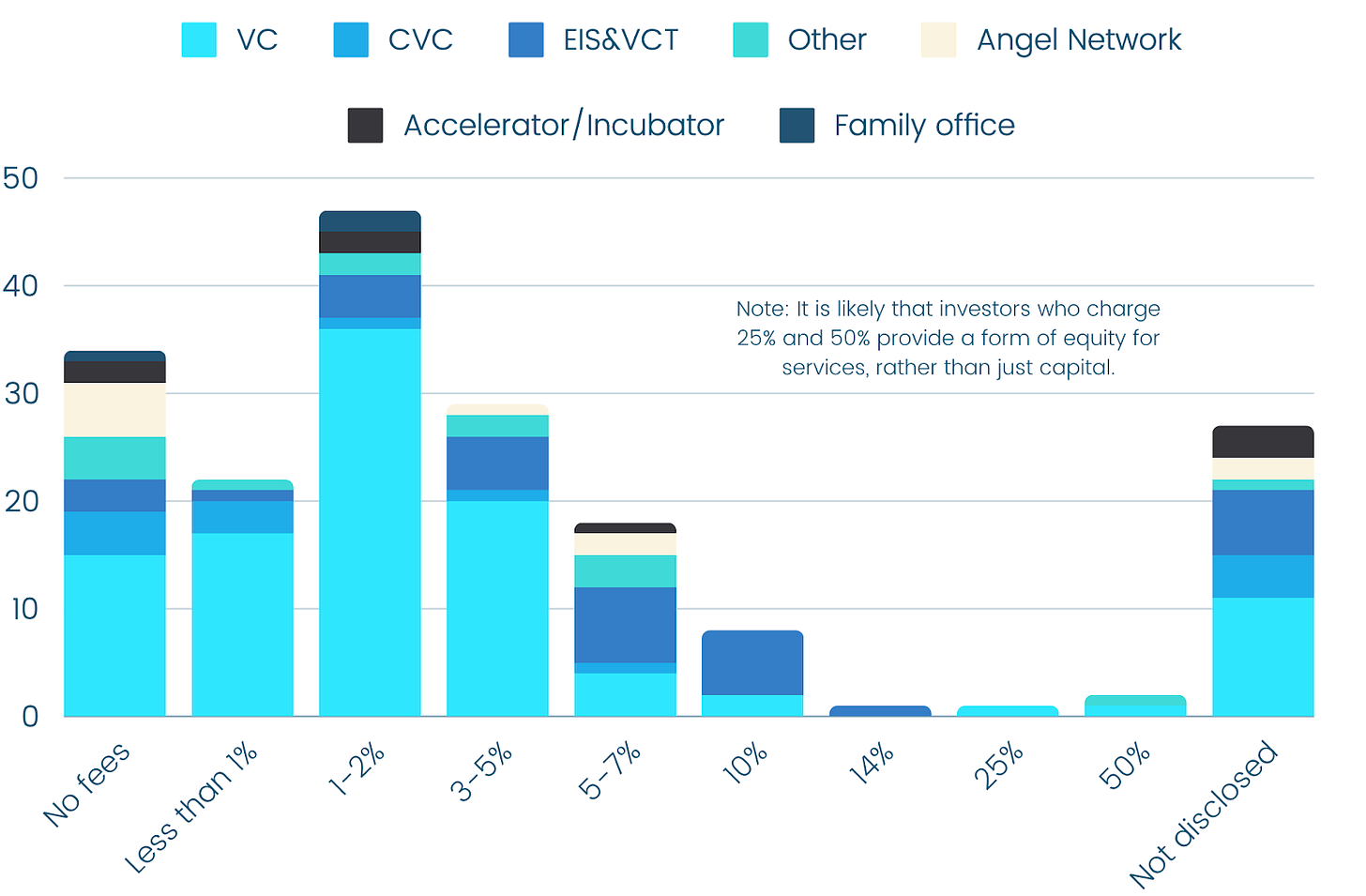

Am I just cherry-picking a few bad examples? A Europe-wide survey of term sheets called out this practice specifically in the context of EIS and VCT funds, precisely because it’s unusual.

And EIS and VCT over-representation in the high fee bracket is stark.

The same founder I spoke to above saw their angel syndicate charge 5% upfront. One member of the syndicate pushed them hard to use a specific lawyer (a friend of theirs) to manage the round, who charged exorbitant fees. When the founder complained about the fees to the syndicate, they were told: “If you think these fees are high, wait until you have to pay private school fees”. The level of empathy any founder wants from their investors.

“We asked some investors if they liked tax breaks and they said…”

Considering billions of pounds have flowed through EIS and VCT since their inception, you’d assume the government would be keen to understand how well they worked. Right?

Wrong.

Despite tens of billions of pounds having been invested through these schemes, the government has been … incurious. The closest thing we have to a recent evaluation came from HMRC in 2022. This ‘analysis’ is a perfect encapsulation of the “We asked people with a vested interest if they like free stuff” archetype of policy work Anastasia and I described a couple of weeks ago.

The evaluation primarily consists of asking people with tax breaks if they like tax breaks (yes they do) and businesses dependent on said investors’ money if they would rather be insolvent (no they wouldn’t). Other questions include HMRC asking fund managers if they believe they perform rigorous due diligence (yes) and investee companies if their work is innovative (also yes). Surprise!

This bracing interrogation did reveal a few interesting tidbits. Namely, that the primary motivation for investors is indeed the tax incentive and that the majority of the recipients admit that their businesses would have struggled to keep the lights on without the support.

If a business is unable to keep the lights on without money provided as a result of tax incentives (and on potentially disadvantageous terms), this is likely a reflection on company quality. At least in some cases. HMRC does not consider this scenario at all and instead frames these results as an example of policy correcting a ‘market failure’ and asserts (with no evidence) that: “Unregulated free markets will likely under-produce innovation.”

The evaluation also uncritically repeats a series of complaints from founders about VC. These include that i) it’s inaccessible if you’re not based in London, ii) small cheque sizes aren’t available, and iii) all investors want immediate significant dilution. All claims that can be judged with empirical evidence (and are incidentally all untrue), but HMRC decided not to check.

What’s totally missing is any assessment of EIS/VCT recipients’ actual contribution to the UK economy or whether the scheme represents value for money to the taxpayer.

Taking a step back

If the government isn’t going to take the time to analyse this work seriously, has anyone else?

There isn’t a stack of academic evidence and much of it is quite old. One 2009 study went as far as describing these schemes as “largely an act of faith by governments” and cautioned that insufficient work had gone into developing evaluation methodologies. Their warning went unheeded.

While EIS remains hard to assess, there is slightly more academic work around VCTs. This largely underscores the self-defeating elements of the scheme’s design.

For a start, the VCT market is stunted by low levels of liquidity. The rationale for making VCTs public limited companies (rather than real trusts) was to reduce the risk of holding unquoted assets by creating a secondary market with liquidity.

But as one 2011 study observes, there is no meaningful secondary market for VCT shares. By not extending VCT tax advantages to secondary purchasers, trading volumes remain low and a meaningful bid-ask spread (the difference between the highest price a buyer is willing to pay and the lowest price a seller is willing to accept) opens up during the holding period. These range from 6% up to more than 30%. With most commonly traded shares, you’d expect less than 1%. Considering the small returns many investors make on VCTs, even a 6% spread could wipe out most, if not all, of their gains.

This has been reaffirmed by more recent research and is obvious when you look at VCT shares through a brokerage platform.

This is something providers don’t hide. In prospectuses, funds will usually include a disclaimer along these lines:

Although the existing Shares have been (and it is anticipated that the New Shares will be) admitted to the Official List and are (or will be) traded on the London Stock Exchange’s market for listed securities, the secondary market for VCT shares is generally illiquid. Therefore, there may not be a liquid market for the Shares, which may be partly attributable to the fact that the initial income tax relief is not available for VCT shares generally bought in the secondary market and because VCT shares usually trade at a discount to their net asset value, the price of the Shares may be volatile and Shareholders may find it difficult to realise their investment. (Source)

Why does this matter?

When investors can only sell at a significant discount, VCT managers are, in practice, unlikely to be punished for poor performance. While I’m indifferent to the fate of the median VCT investor, it’s not only unhealthy for the government to subsidise the distorted allocation of capital, it’s also the exact opposite of what the policy was supposed to do!

It’s not just liquidity. Even relatively early analyses of the VCT scheme were warning that the focus on tax relief was causing VCTs to underperform standard VC funds. This study pointed to the time constraint of the tax year leading managers to rush the due diligence process and invest in poor opportunities to use up leftover cash.

Solutions

It was wrong of the government to renew these schemes without assessing their effectiveness. But there is precedent for change.

EIS’s predecessor, the Business Expansion Scheme, ran from 1983 to 1994. It was replaced because the government believed that it had primarily become a tax avoidance vehicle, rather than a means of supporting businesses. EIS and VCT have gone on the same journey.

The justification for maintaining the status quo at a time when the UK’s early-stage VC ecosystem is one of the largest in the world feels thin. The original problem these schemes were created to solve increasingly doesn’t exist.

The case for preserving VCT is particularly weak. The scheme itself attracts fewer than 30,000 investors a year and funds’ dismal performance figures suggest it adds little to the world. I would recommend removing all tax relief for VCT investment. These vehicles would likely die and, quite frankly, Britain wouldn’t be the poorer for it.

When it comes to EIS, there’s grounds for partial preservation as part of a reformed system.

Funds or syndicates that charge anything beyond minimal fees (e.g. legal costs) to investee companies should be barred from the scheme. I would also favour withdrawing the income tax, loss, and IHT relief for all investors, while maintaining the capital gains exemption. This would make the scheme cheaper and drive out many of the bad actors and middlemen. Those left would be better aligned with founders trying to build long-term winners.

It also may be worth revising who is eligible to claim EIS relief. At the moment, the scheme is primarily used by wealthy retail investors who’ve maxed out other tax-free vehicles. While there will be exceptions, I question the extent to which the median lawyer, accountant, or management consultant will ever be a particularly valuable addition to a cap table. The US has a thriving ecosystem of founders and operators who act as angel investors and bring relevant expertise to investee companies. They’re motivated by a desire to make outsized returns, not by the tax system.

Much of the bad behaviour I’ve described in this piece isn’t confined to EIS and VCT. There’s a longer piece to be written looking at how bad practice, founder unfriendly behaviour, and short-termism remains prevalent in the wider UK ecosystem. Unfortunately, the government, which props up or directly subsidies so much of this bad practice, seems indifferent. It publicly proclaims the UK to be one of the world’s leading venture ecosystems, while giving it the kid gloves treatment you might expect for an emerging sector.

It’s time for us to decide - are we serious or not?

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer (Air Street Capital), my friends, barber, or the four people who follow me on Strava. This is not financial advice. Don’t arrange your finances based on strangers’ Substacks. I have never used (S)EIS (either directly or via a fund), nor have I ever held long or short positions in any VCTs or VCT-backed companies. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

There’s also SEIS, for earlier stage innovation, which operates on the same principle as EIS, but with a lower relief ceiling and a higher rate of income tax relief. I don’t cover it in this separately piece, just because it’s significantly smaller and the investment limit per company is very low. Many of the same criticisms, however, hold true.

Substack gets mad at me if I link to the accounts in full because of URL length, but if you want to check, click through to the 2020 and 2021 accounts on the Companies House page.

I’m afraid you have to sign up to get the full table, but on the plus side, they don’t spam you.

Totally right, Alex. It's one example of how the UK government has (over time) constructed a startup ecosystem that seems designed to generate far too many low or zero outturns. There are others too - IUK grant competitions, heavy R&D tax credits, poor targeting of nations & regions funding to fee-driven 'venture' funds....

Strong agree on this - short-term incentives on EIS should be binned IMO. They should invest that money in stuff that will actually create more valuable startups & economic growth, like reforming planning regulation, better salaries for civil servants and frontier research.

The cap gains treatment is good and is a smart incentive for people interested in playing long-term games of value creation.

However, separate point - I'd be curious to see how performance of many institutional VCs in Europe matches up against this. Often not any better, I would wager. The ecosystem has a similar problem as a whole, very much subsidised by the government and not delivering the value it should.