Cultural vibes aren't analysis

Economic reality, not vibes, explains Europe’s lack of big tech companies

Introduction

If you spend enough time around enough founders and investors, you’ll quickly discover that one of the most popular explanations for Europe’s relative lack of big tech companies is ‘culture’.

Tom Blomfield, the co-founder of Monzo, articulates this view well:

“In the UK, the ideas of taking risk and of brazen, commercial ambition are seen as negatives. The American dream is the belief that anyone can be successful if they are smart enough and work hard enough. Whether or not it is the reality for most Americans, Silicon Valley thrives on this optimism”.

I’ve heard versions of this expressed by countless other successful people, but I’ve always found “something something American dream”, “in the US people build”, “there’s an appetite for risk”, “being wealthy is seen as aspirational” and the many, many variants thereof to be unsatisfying explanations.

In fact, 99% of the time, cultural explanations of economic divergence, especially when it comes to big company creation, just read like people projecting their personal ideological hang-ups onto either a European or American Other.

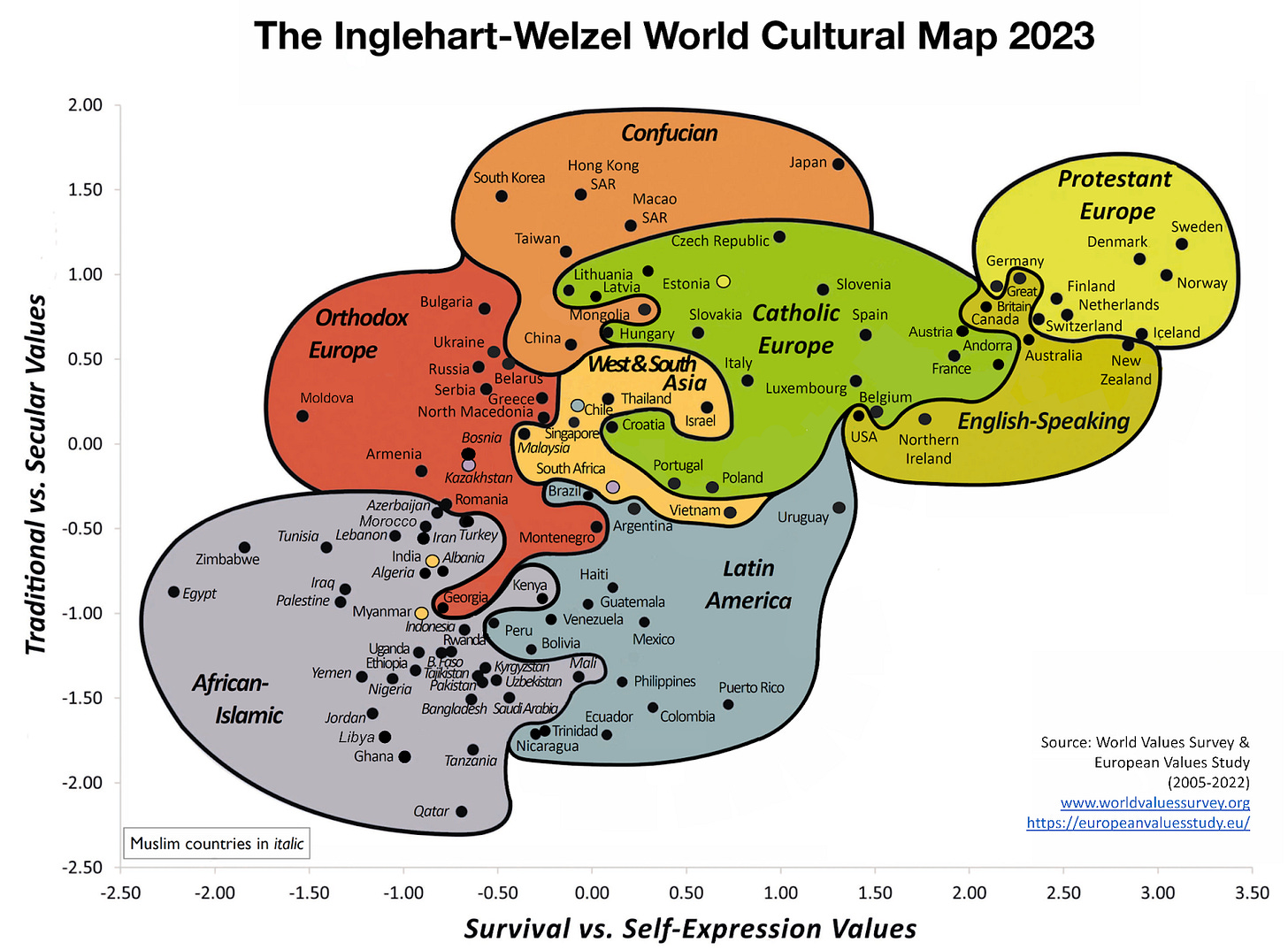

To be clear, I’m not trying to argue that culture doesn’t vary between societies. That would be silly. If we gathered a group of people from Amiens, Atlanta, Armagh, and Amman in a room - their outlooks on the world would likely diverge significantly.

But at the same time, this has produced an industry of takes that are practically … useless. My contention is that cultural theorising is a poor way of explaining Europe and the US’s divergent economic performance, ability to scale companies, and a lot of other things. It encourages defeatism and a fuzzy view of policy. This week, Chalmermagne goes Marxist and makes the case for remembering on the economic base.

Explanation or ideological bias?

With the greatest respect, neither founders nor VCs tend to be gifted historians or macroeconomists. Nor do they need to be. This is why their analysis of economics often feels like vibes-based extrapolation from the traits of people they admire.

By their nature, the most successful founders are highly unrepresentative on just about every metric. If someone has built a multi-billion dollar company, they are freakishly talented and driven, intensely lucky, or a criminal. Or a combination of the above. Whichever way you cut it, they tell you next to nothing about the median person in their society. Thanks to the strength of the US tech ecosystem, Americans are likely over-represented in this sample.

These cultural explanations are then commonly repeated as if they’re self-evidently true.

For example, a common contrast you’ll hear is between American respect for success and British ‘tall poppy syndrome’, where us Brits have to cut down anyone newly wealthy we know due to a vague theory about the class system.

This conveniently ignores the widespread popularity in the US for greater taxation of the wealthy. Close to two-thirds of Americans have expressed support for a wealth tax on the super-rich. A similar proportion believe the gap between rich and poor is too wide. These aren’t that different to the statistics we see in the UK - with a pro-wealth tax organisation (a group incentivised to find the highest possible number) finding a similar proportion in favour of a tax to our US survey.

But even if the UK number was significantly higher, would this have really have significant explanatory power? Are the people who build generational companies actually dissuaded by a loose sense of their neighbours’ jealousy?

We can apply the same test to a bunch of other cultural markers.

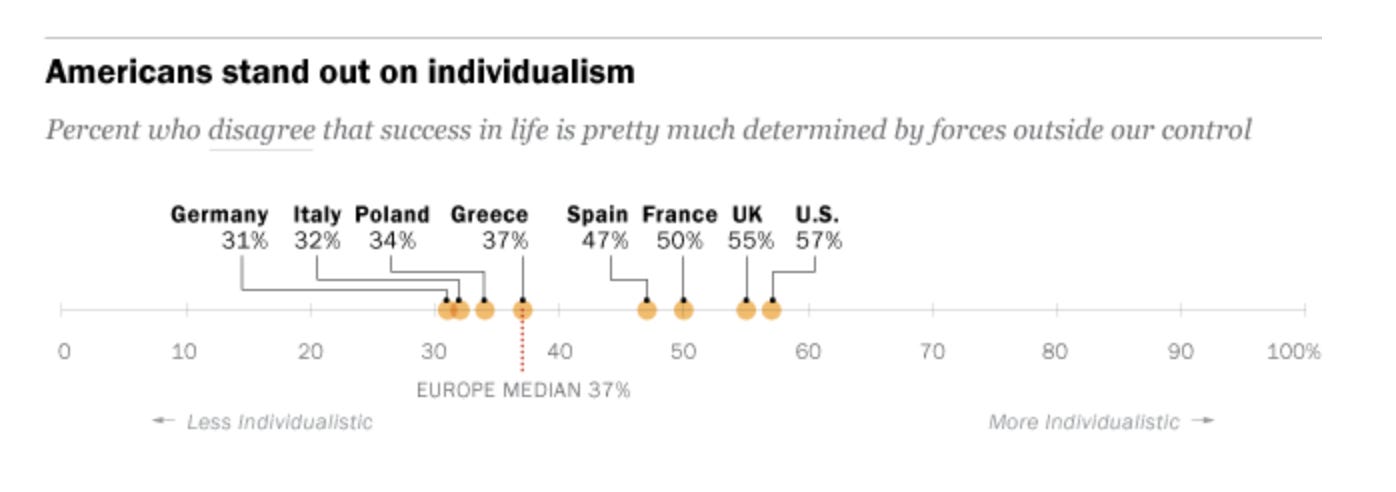

Let’s take individualism.

Americans are indeed more likely to believe their fate is in their own hands … by a whole two more percentage points than the UK and seven than France. Maybe those two points make all the difference, but colour me sceptical. The US beats Poland by 23 points on this measure, but Poland has also been one of the continent’s great economic success stories. Self-reported individualism might be an example of a cultural difference, but does it predict anything useful?

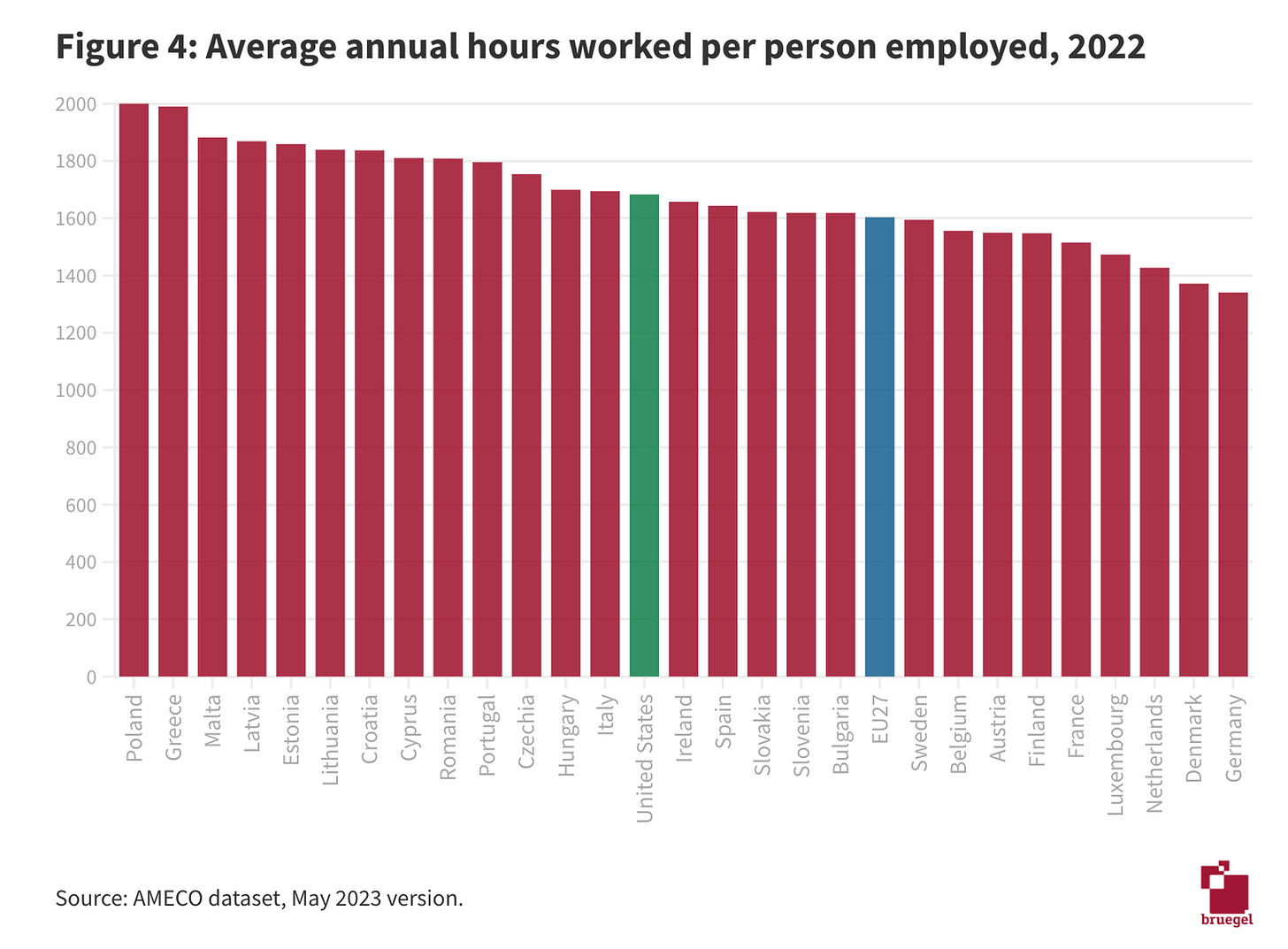

Do Americans have more of a work ethic than Europeans?

Slightly, but not as markedly as you’d expect based on popular perception. And significantly less than the anti-individualist Poles we were discussing above.

Three economic factors in a trench coat

Now, of course there are important differences between America and European countries. But to what extent are ‘cultural differences’ really best explained ‘culture’?

Let’s take employment rights as an example.

It’s true that the US has much weaker employment protections than essentially any European country. You can assert with a reasonable degree of confidence that strong employment protections come with a trade-off around business dynamism.

If it’s time-consuming and expensive to get rid of people who underperform or who you no longer need, you’re likely to be more cautious about hiring. Similarly, if your company has to pivot to a new business model or technology, stringent employment laws make it hard to adjust your team accordingly.

The cultural explanation would be a version of: people in European nations place a premium on stable employment and they are prepared to sacrifice a degree of economic dynamism to preserve this.

Now, there’s probably some truth in this. If you give people a lot of employment protections or subsidies, they will be reluctant to hand them back in exchange for a hypothetical increase in GDP growth. This isn’t a uniquely European characteristic - just look at the unreformed and increasingly unaffordable US entitlement system. The frontier spirit apparently doesn’t extend to social security or Medicare.

This is because path dependency, rather than culture, is likely a better explanation of the difference.

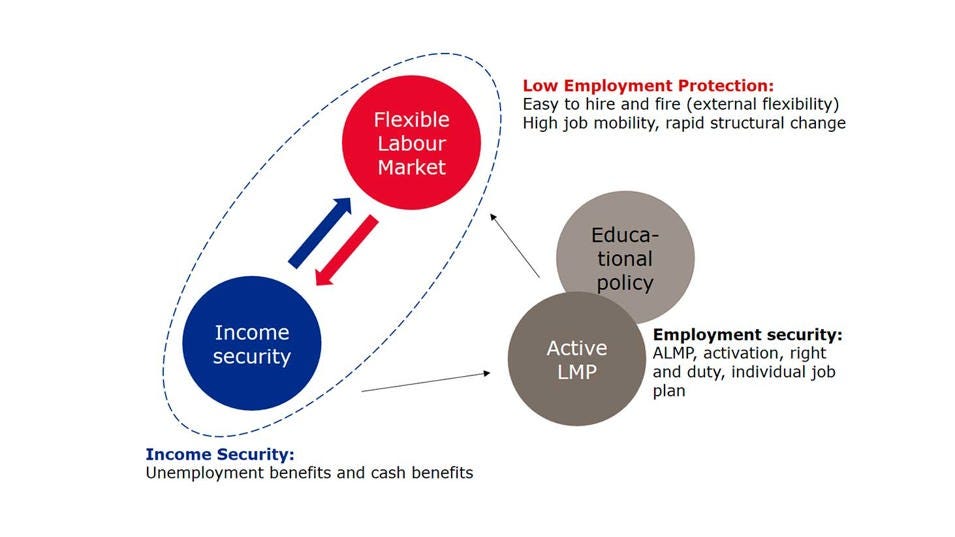

You see this really clearly when you dive into individual examples. Denmark is known for its relatively unusual system of ‘flexicurity’, where employers are able to hire and fire easily, while the unemployed are able to benefit from a generous safety net. This means churn is reasonably high in the Danish private sector.

But Denmark otherwise has a more typical ‘Scandinavian’ welfare system. This suggests ‘culture’ is a weak explanation, so how did it end up in this unusual position?

In short, after some particularly ugly strikes and an ensuing lockout in 1899 essentially drained both the unions and employers of resources, the two sides agreed to a compromise where employers retained flexibility in hiring/firing decisions while unions gained influence over wages and working conditions through collective bargaining. This framework was established outside the government. Meanwhile other European countries tended to be left with a more binary choice between strict employment protections or limited welfare provision.

The US, in turn, benefitted from … a combination of the New Deal and not being economically decimated by World War II. As European nations rebuilt their economies and constitutions from scratch, scarred by the memory of the Great Depression, they were sympathetic towards social-democratic policies and strong unions. The US felt no need to change course and give the workforce a greater role in economic governance.

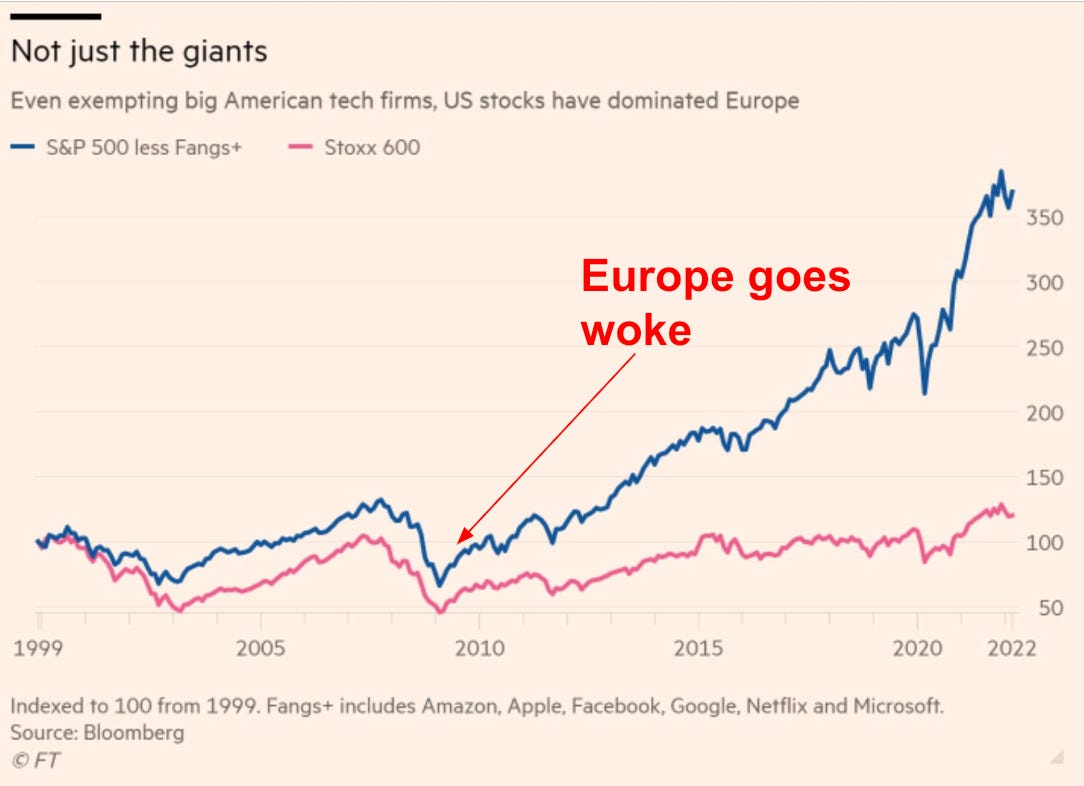

Cultural factors also struggle with time - there have been moments when US and European performance on any number of economics have aligned, and times when they’ve diverged. During the mid-to-late 90s, for example, both regions saw remarkably similar patterns of strong economic growth, low inflation, falling unemployment, and strong equity markets. Can culture really have changed so much in the last couple of decades?

If we go back to the Tom Blomfield quote at the beginning, is risk tolerance really best explained by culture?

His piece opened with him questioning why talented US graduates seemed more inclined to work in start-ups, while their British peers tended to take jobs at McKinsey and Goldman Sachs. The vibes in Oxford or Cambridge are almost certainly different to those in the Bay Area. But it’s also true that the US has the world’s most mature technology ecosystem, with a large number of high-profile success stories. Smash hit UK start-ups and repeat founders are rarer, while the UK is one of the leading markets for financial and professional services.

But why not use ‘cultural factors’ as a short-hand for the effects of these historic economic forces?

In short, because it isn’t helpful. These differences were the product of policy decisions, not cultural vibes. That means that they can be changed via politics if necessary. There is nothing ineffable about European-ess that leads to a specific regulatory regime for employment rights, or basically anything else. For the vast majority of economic issues, ‘culture’ leads us into an analytical cul-de-sac.

Uninventing economics

Even if we shift a few policies, with reforms to procurement here, or changes to employment law there, Europe is still confronted by the glaring challenge of … reality.

In the discussions about companies not scaling domestically or fleeing overseas, investors and founders often forget good old-fashioned economics.

Comparative advantage, formalised in the early nineteenth century, accepts that trade patterns are generally determined by relative rather than absolute productivity differences. Even if one party is better at everything (absolute advantage), both parties benefit when each specialises in what they're comparatively best at.

It will often just make more sense for entrepreneurs to scale companies in a country with a bigger market, looser employment laws, lower energy costs, and the vast majority of the world’s best academic institutions. As a result, people are more likely to want to raise growth rounds from established US funds that can help them plant roots on the other side of the Atlantic.

Now, Europe could address some of the underlying causes of the US’ comparative advantage in scaling.

It could, for example, increase the size of its market by tearing down its internal trade barriers, which according to the IMF, are the equivalent of 45% for manufacturing and 110% for services. There’s currently the EU Inc. effort underway to campaign for a Europe-wide entity for start-ups.

Additionally, EU member states could push to weaken overbearing tech regulation, whether it’s GDPR or the EU AI Act.

European countries could fire up nuclear power stations to bring down persistently high energy prices, unless they fancy another stint of Russian natural gas dependence.

But to do so, it needs to decide why it wants to and develop an underlying theory of how to incentivise and foster big company creation. There are perfectly reasonable theories about why both of these are good, but I’m yet to hear many European governments articulate them. Instead, they’ve opted to pump more and more money into a pale imitation of the US venture ecosystem, so it can sit in more undifferentiated SaaS companies with a limited footprint.

Culture or legacy?

Having said all of the above, I regrettably don’t believe that if we just pull a few economic levers, everything will magically be fine.

There are certain biases that need to shift that I will grudgingly accept are cultural. I distinguish these from the policy and economic changes we covered above, because there aren’t simple policy levers that can be pulled. They’re ingrained habits that aren’t downstream of political decisions. These will likely only be resolved by a change in mindset.

A major bias is the mercantilist way many European governments, academic institutions and start-ups approach intellectual property. They routinely mistake IP hoarding for value capture.

For example, in the UK, the House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee recently published a report, which warned that “we have consistently struggled in enabling our brightest technology startups to transform into significant domestic businesses and potential British world-class companies … the consequences of this failure are significant”. Baroness Stowell, who chaired the committee, wrote in an opinion piece that:

There can be no doubt that British tech unicorns galloping overseas as they reach maturity is damaging to UK PLC. Decreased global competitiveness, weaker economic prospects and a ‘brain drain’ of talented individuals are all likely consequences of failing to support our companies to scale at home.

This is a serious problem, especially for a Government that has declared economic growth to be its number one priority. We can and must do better than act as an ‘incubator economy’ for countries with greater ambition.

The ‘incubator economy’ framing isn’t just theoretically unsound, it also overlooks how the economic benefits of innovation diffuse. Historically, only a miniscule proportion (~2%) of the gains created by technical advances are captured by their producers, with the rest going to consumers. After all, the creators of the printing press were not the main beneficiaries of its invention. In fact, early adoption of a German invention in Holland led to local innovations that were in turn exported back to Germany.

This is because (with the exception of a few industries) most innovation is expensive to produce initially, but comparatively inexpensive to reproduce, adapt, and distribute. This is particularly obvious in a field like AI. If you have the budget and the team, it’s often surprisingly easy to reverse engineer other people’s breakthroughs. We’ve seen this with the run of reasoning models following OpenAI’s o1, along with rapid replications of Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold 3.

This isn’t unique to the UK. A different spin on the IP problem emerges in Wolfgang Münchau’s Kaput, which documents the souring of the German economic miracle. In Münchau’s telling, the historic success of Germany’s industrial heritage and export-led growth model bred intense complacency. The German car industry, for example, did everything it could to resist the shift towards electric vehicles and the growing importance of AI. German incumbents prided themselves on their international leadership in … the number of patents and responded to fresh competition via a combination of cheating and calling for tariffs.

You even see a version of this in some European start-ups. A number of the continent’s most high profile anti-success stories were the result of companies concentrating too much effort on their IP and ignoring such prosaic questions as customers and product. Perhaps the peak example of this is Graphcore, the AI chip company, which combined elegant hardware with janky homebrew software. This is a mistake that NVIDIA would never have made.

This bias in turn leads governments to pursue value-destroying policies, designed to keep innovation domestic - whether it’s exit taxes, M&A restrictions, or ever-greater subsidy of the venture market. The sense of relative decline and faded past glory is a powerful drug.

Closing thoughts

So where does this leave us?

There are broad strokes variations in cultural bias that explain underperformance in certain sectors. People with those attitudes should get swept away with time. But ultimately, path dependency is real. What seems like an ineffable vibe is often better explained by an economic crisis, bad policy decision, or 19th century collective bargaining agreement you’ve long forgotten about.

Next time you want to comment on a trend: ask yourself, is this best explained by policy, institutions, and history, or by collective bias?

Maybe it’s a bit of both.

But as a moderate, temperate Englishman, I would say that, wouldn’t I?

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer, people I run past in the street, or anyone else. I’m not an expert, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned.

I broadly like & agree with this characterization! One note though —

> The US, in turn, benefitted from … a combination of the New Deal and not being economically decimated by World War II. As European nations rebuilt their economies and constitutions from scratch, scarred by the memory of the Great Depression, they were sympathetic towards social-democratic policies and strong unions. The US felt no need to change course and give the workforce a greater role in economic governance.

This is path dependence, sure, but it's also the way that historical circumstance affects political culture (more sympathy/support for social democracy + worker protections), which then gets institutionalized as policy, right? I think culture & its perpetuation does matter — but that its origins are deeper than surface-level personality traits (e.g. tall poppy syndrome) + policy is often required to "lock it in"