A bridge fund to nowhere?

The UK government, venture capital, and 23 years of bad public policy

Introduction

“British investors targeted in first government advertising push for scale-up boost” blared out the headline of the UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology press release that landed in my inbox back in March of this year. You can imagine my excitement as I learned that:

“Targeting investors in key financial hubs across the country in cities such as London, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Belfast and Cardiff, the campaign will run on billboards strategically placed 200 metres within investor offices and on key commuter routes. Wrapped copies of The Times will also be delivered to venture capital offices, and digital adverts will run online and across podcasts.”

Seven months later, I remain bitter that my wrapped copy of The Times failed to materialise. This absurdity, however, did not occur in a vacuum. As we see with the current hectoring of pension funds and asset managers to invest in UK equities, attempting to browbeat the financial sector into serving policy goals is currently in vogue. But it’s not new.

From the earliest days of the venture capital industry in the UK, successive governments have attempted to do exactly this. As ‘industrial strategy’ comes back into fashion, I believe the story of the UK government’s patchy efforts to mobilise and shape the industry can teach us a few lessons about incentives, policy design, evaluation, and the distorting effects of lobbying.

Things can only get better?

Until the 1980s, investing in small private companies was a peripheral activity undertaken by a few banks. The Thatcher era brought deregulation, as well as tax relief for early-stage investment. Firms also benefited from the creation of the Unlisted Securities Market in 1980 (the precursor to the AIM), an exchange for small firms with less than three years trading history. The emerging venture boom in the United States likely didn’t hurt either. UK VC firms went from investing £20 million in 1979 to over £1.6 billion in 1989.1

The 1990s in turn saw the birth of a number of schemes that exist to this day, including the Enterprise Investment Scheme and Venture Capital Trusts. The former offered investors in early-stage ventures significant downside protection via tax breaks, while VCTs opened up tax breaks for individual investors in VC funds.

In this era, while the government rolled the pitch in the industry’s favour, it stayed on the sidelines.

This all changed with the return of the Labour Party to government in 1997. In its first term, the Blair Government created a series of vehicles to channel hundreds of millions, and later billions, of pounds of public money into early-stage businesses.

The government was motivated by a desire to close the ‘equity gap’ - the situation where the capital needs of some early-stage businesses are too high for angels, too risky for banks, but too small to attract VC firms.

Originally a complaint dating back to the Great Depression, it received fresh urgency when the Bank of England in 1996 and the Confederation of British Industries in 1997 published reports warning that the growth of the VC industry in the UK had done little to help emerging tech firms. A common criticism was that the industry disproportionately focused on later-stage, lower risk activity like management buy-outs, rather than supporting innovators.

A 2003 Treasury Report argued that this gap was severe for businesses seeking up to £2 million and warned that: “This equity gap is a barrier to productivity growth, as it can stifle the development of innovative start-up and early-stage businesses, and can constrain the supply of capital for some established businesses that are seeking to modernise or diversify their activities.”

Outlined in a 1998 white paper on competitiveness, the new Labour Government spun up a number of initiatives, designed to use government money to crowd in private investment. These included:

UK High Technology Fund - a £126 million fund of funds, catalysed by a £20 million government commitment, which invested in nine funds.

Regional Venture Capital Funds - £226.5 million invested over nine funds, designed to showcase the potential for private sector investors to achieve a commercial rate of return outside London, featuring £74.4 million of public money.

Bridges Funds - £40 million fund for investment in the 25% most disadvantaged areas of England, half of which was provided by the government.

Early Growth Funds - £91 million, catalysed by a £26.5M government commitment, to demonstrate the potential of investing in early growth businesses.

There was an attempt

These efforts did not succeed. While the government remained cagey about performance, a 2009 National Audit Office review was scathing.

It found that the UK High Technology Fund’s interim internal rate of return was -9.7% and the RCVFs’ -15.7%, while the Bridges Fund had performed a little better at +7.7%. Bridges, however, had far fewer constraints on its investment activities and (bizarrely) was able to invest in property, which became the primary driver of its returns.

To lure in private sector investors, the government had agreed to bear the brunt of any losses and to offer them preferential treatment in the event of any returns. This meant that the original £74 million public investment in the RCVFs was worth £5.9 million - a -93% return on investment.

All the while, the department was paying out fees to professional fund managers, which ate up 36% of the money invested in the RCVFs, 17% of the High Technology Fund, and 29% of the total invested in the Bridges Fund.

Even before the NAO report, there were red lights on the dashboard. In 2007, when the RCVFs had been up and running for six years, half the capital remained uninvested and the external managers were complaining about a lack of suitable management teams in some regions.

The manager in the north-east said that “it has been tough getting the money out there”, while in the East Midlands warned that “there is no lack of capital, but there is a lack of good management teams to invest in”. The government’s defence was that “some 283 SMEs have been supported so far, indicating an ongoing requirement for equity investment of [this] type”.

This is a wrong-headed argument that remains a staple of policymaking to this day.

Firstly, the act of spending money is a bad metric for … somewhat obvious reasons.

Secondly, if these teams or businesses were genuinely good, there is a chance that the government may have just succeeded in crowding out private investors.

In fact, research was already appearing in Europe from the mid-noughties pointing to how government investors that were simply content to receive their money back were crowding out more disciplined private investors. One study of fourteen European countries found that every additional dollar from government funds led to a dollar less from their private counterparts.2

But was government content just to receive its money back?

Well, we just don’t know. As the NAO put it: “no clear financial objective was set for the impact of the funds to the taxpayer, such as whether they were expected to break-even and over what timescale, and the Department did not specify objectives for wider economic benefits apart from the Bridges Funds” and noted that they had made no attempt to evaluate the funds in eight years.

This was backed up by one RVCF manager at the time, who said in 2006: "I wonder whether the publicly backed funds aren't doomed to fail. On the one hand they are supposed to be about fostering entrepreneurship but on the other they are supposed to make money. In some respects these are conflicting objectives. Certainly they pull in different directions.''3

Mr Anonymous Fund Manager points to a central tension in UK government policy on venture capital - the lack of clarity around objectives.

Is the purpose of this support to back strategically significant proto-winners or to act as a small business financing scheme?

The real equity gap was the friends we made along the way

Based on its heavy use of narrow regional constraints and choice of evaluation metric, it appears to be the latter. The other real ‘tell’ is that when you look at the big technology strategy documents from the government in this era, this work is simply not mentioned in them, beyond the odd passing comment. If the purpose of this work was to back strategically important companies, then there’s no written evidence of it.

This makes venture funding almost certainly the wrong vehicle. Discussion of the equity gap often focuses on the inability of ‘viable’ businesses to get money - in fact a current civil servant used exactly this turn of phrase when we were debating this on X.

But ‘viable’ means different things to the management of a small business and a partner at a VC firm. VC is not suitable for most enterprises: unless a business has the potential to be a runaway success story, investors simply can’t justify the risk of backing them. Turning a profit and becoming a respectable regional employer is great, it’s just a different thing! Confusing these definitions of viability results in attempts to leverage a type of financing for a purpose it was never intended for.

The evidence base that there was this ‘equity gap’ that needed plugging by the government was, at the very least, contentious.

When these policies were first devised, there was no comprehensive database of VC transactions in the UK. Rather than asking investors for data, the government heavily relied on asking businesses if they were able to raise all the money they needed from investors.

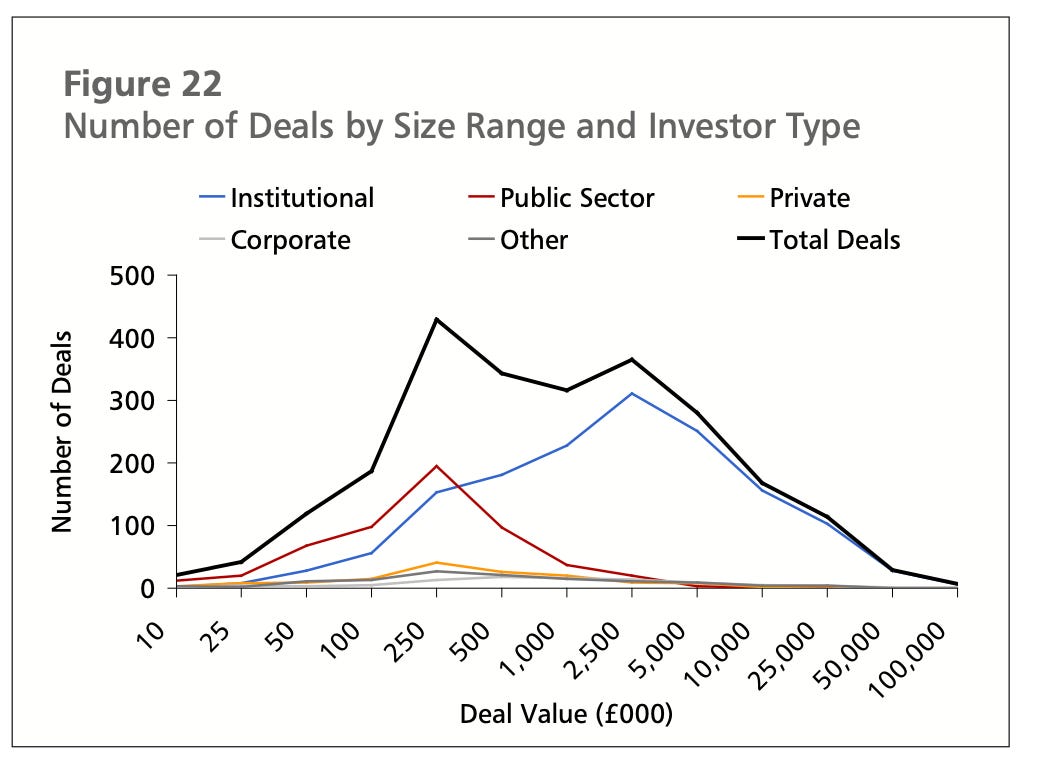

In 2006, now-defunct research firm Library House created a transaction dataset for the first time. They found that there was no shortage of deals in the £250k to £2 million range and that “there is no ‘gap’ in the range of funding deal sizes available to growing companies in the UK”.

As they put it: “A comparison of the funding requirements of companies with subsequent funding received shows that a significant gap remains between desire for funding and actual investment. However, this phenomenon is only partially related to the level of funding available and is more reflective of the fact that the majority of companies seeking funding simply do not have the potential required to warrant investment by an investor motivated by financial gain.”4

Yet, they persisted

Did the government learn from these early mistakes? Yes and no.

Even before the NAO report dropped in 2009, some of the government’s work was trending in a more promising direction. From 2006 onwards, the government began acting as an anchor investor in new VC funds via the Enterprise Capital Fund programme. This has helped bring around 30 new fund managers into business and its performance has fared significantly better than its predecessor initiatives.

The British Business Bank, which took over the management of this work after its creation by the Coalition Government, commissioned a third party analysis of the ECF scheme in 2021. It concluded that each £1 of cost brought £2.62 in net economic benefit. I have my gripes with the methodology employed, which largely consists of stringing together a bunch of correlations, but we can see from the accounts in the BBB’s annual reports that the scheme is definitely making money.

There is evidence of the scheme helping to bring in genuinely interesting new managers into the business. Its diligence process is thorough, and the BBB draws in private capital by taking less than its share of carry (although it gains downside protection via preferential returns).

However, an unfortunate proportion of this work has gone towards subsiding incumbents who should be able to raise by themselves, or in some cases, had successfully raised funds before the creation of the ECF programme.

The BBB has also ignored the NAO’s call for greater transparency and releases no data on how individual funds have performed. Privately, I’ve heard stories of funds that have literally never returned a penny to investors continuing to receive BBB backing “because they work on deep tech and therefore it’s understandable that they don’t have any DPI yet”. This is expensive SME subsidy reincarnated.

In other areas, there’s more evidence that old habits continue to die hard. Despite its separation from Whitehall, the BBB has not been able to resist the age-old temptation of creating yet more regionally-focused equity financing vehicles, managed by outside fund managers. This is despite the NAO warning against regionally-constrained funds and common-sense logic suggesting a narrow regional focus is bad for diversification.

It’s not just the BBB. An alphabet soup of government bodies clubbed together to create yet another early-stage innovation fund (run by external managers). Troublingly, it points to job creation as one of its metrics of success.

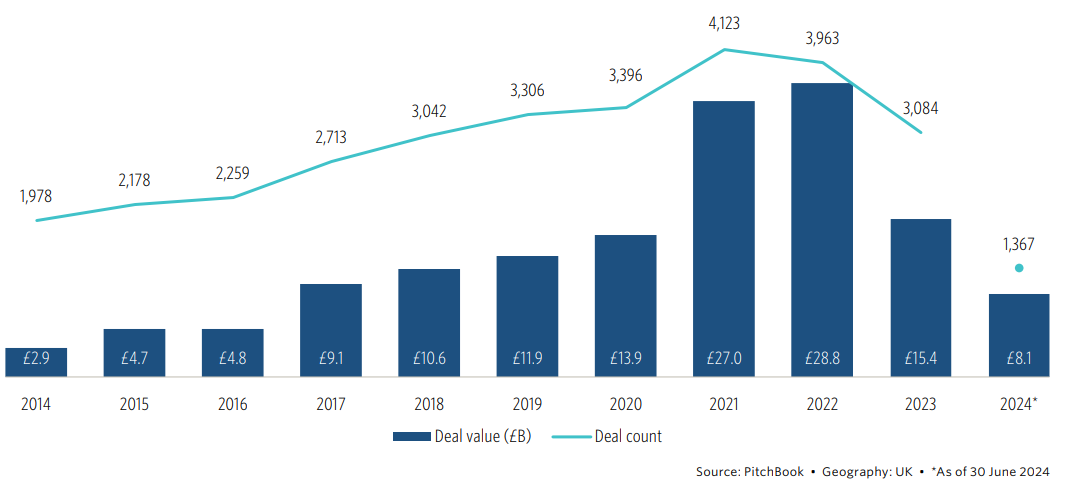

As the UK’s VC industry matured and the early-stage ecosystem exploded, the original ‘equity gap’ thesis became less and less plausible. Instead of being sent to live on a farm (no, you can’t visit it), it mutated. While the ECF programme still employs the ‘equity gap’ as part of its rationale, it has been superseded in the wider discourse by the ‘funding gap’. This is an alleged shortage of growth capital for UK companies.

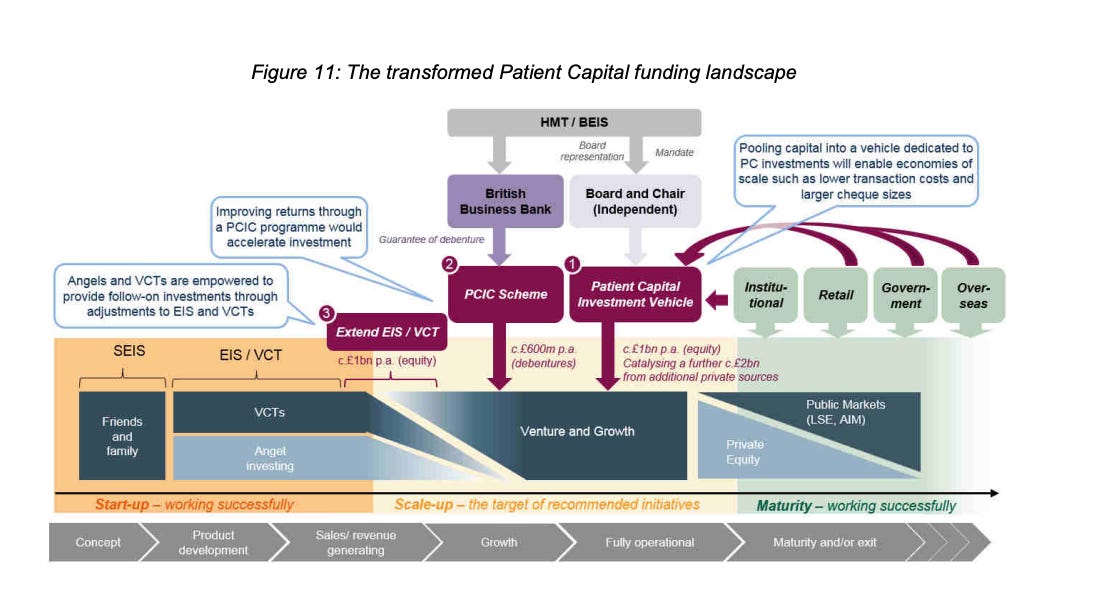

The founding charter of the funding gap is the government’s 2017 Patient Capital Review, the product of much industry lobbying. In this era, investors were upset that promising UK companies often moved to the US when they hit growth-stage, while less promising ones struggled to raise. Instead of judging this as the product of i) some companies being less good than their early investors liked to admit ii) growing businesses consciously choosing US partners who could provide better market access, this was (much like the original equity gap) presumed to be the product of market failure.

The Patient Capital Review, much like earlier work in this genre, eschews any kind of independent economic analysis in favour of consulting a collection of founders, asset managers (including one Neil Woodford), and VCs with vested interests. In short, the government asked a group of people if they wanted the government to mark up the value of their assets - and you’ll never guess what they said!

This led to proposals for a proposed government vehicle that could invest ‘patient capital’, as part of a transformed landscape:

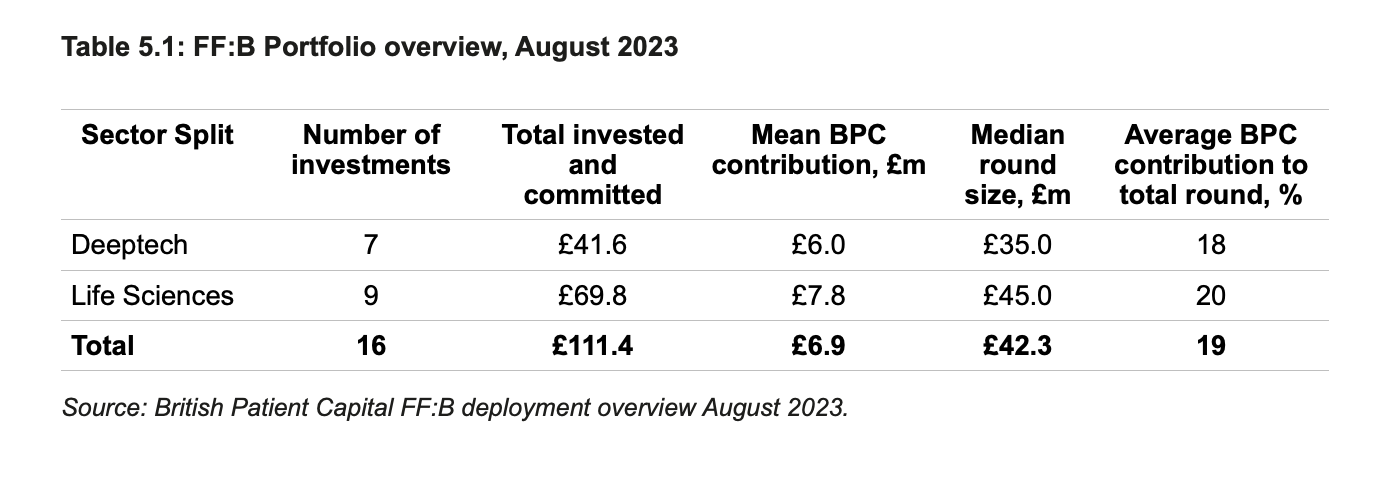

British Patient Capital was duly set up by the BBB, with £2.5 billion to invest in venture funds or directly into promising companies reaching the growth stage. BPC also has the £425 million Future Fund: Breakthrough initiative to invest directly in growth-stage companies.

Catalysing investment… or distorting it?

Thanks to the Cameron and then Sunak-era embrace of technology as a source of economic growth, this work rhetorically has more of an R&D flavour than the SME jungle of New Labour-era initiatives, but there’s still a sense of directionlessness under the hood.

Considering the alleged purpose of this work is to plug the ‘funding gap’ and deliver commercial returns (no potential conflict acknowledged…) it’s worth questioning why government cheques are being thrown into multibillion dollar incumbents that quite obviously do not need the money or why it is anchoring some firms’ fifth funds. In the former case, there is no funding gap. In the latter, it’s worth questioning if a fifth fund that needs government support is likely to achieve commercial returns.

It’s also worth questioning why the BPC is supporting region-limited university spinout funds, which can hardly be judged to be late-stage capital. They also, again, underscore government’s inability to understand the damage regional constraints pose to a venture model where diversification is critical.

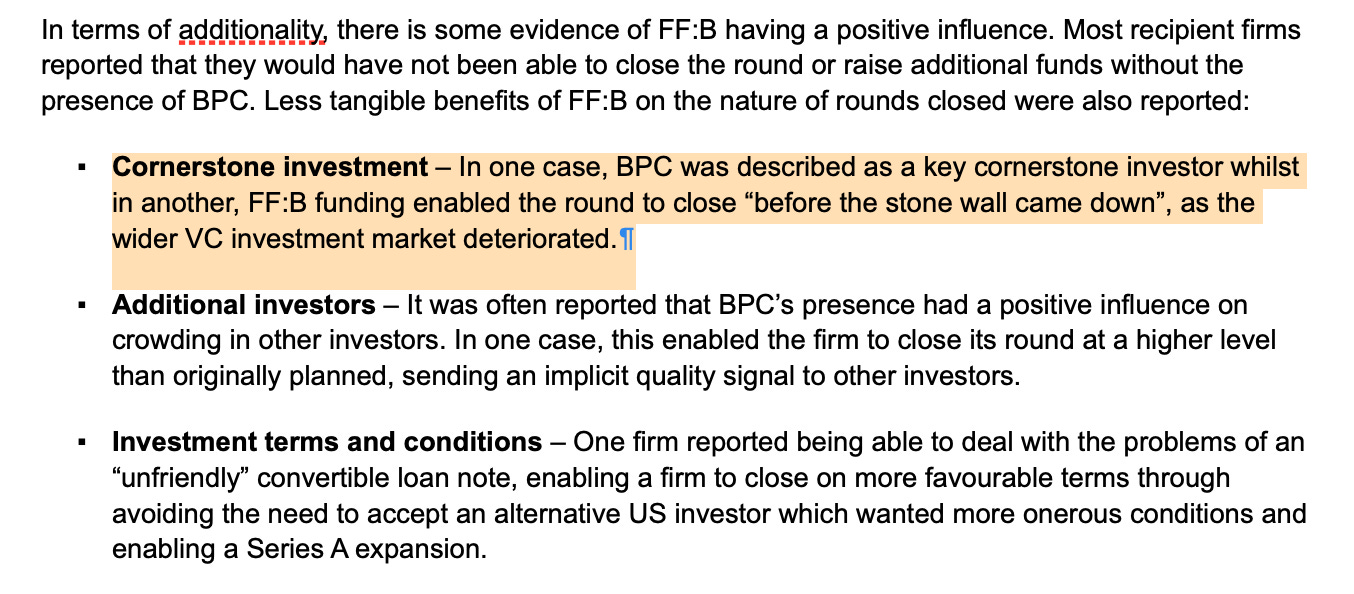

However, The Future Fund: Breakthrough (FFB) is by far the most egregious example of the BBB defying both the logic of the market and common sense. The idea was simple. By acting as an investor in a funding round for a company at growth-stage, the government would give private VCs the confidence to invest their own money, while the final funding round would be bigger. This would help British companies working on crucial R&D to scale, without having to move to the US.

While this might sound logical, it in fact describes the perfect reverse selection mechanism. A scheme designed to bolster companies unable to find investors with conviction is disproportionately likely to select for those with weaker growth prospects. Government is simply creating a false demand signal, preventing the market doing its thing, and talent and capital being recycled in more profitable directions.

The only way this logic doesn’t hold is if you believe that the BBB has a significantly better ability to identify potential winners than private firms - something that even the organisation itself has not claimed.

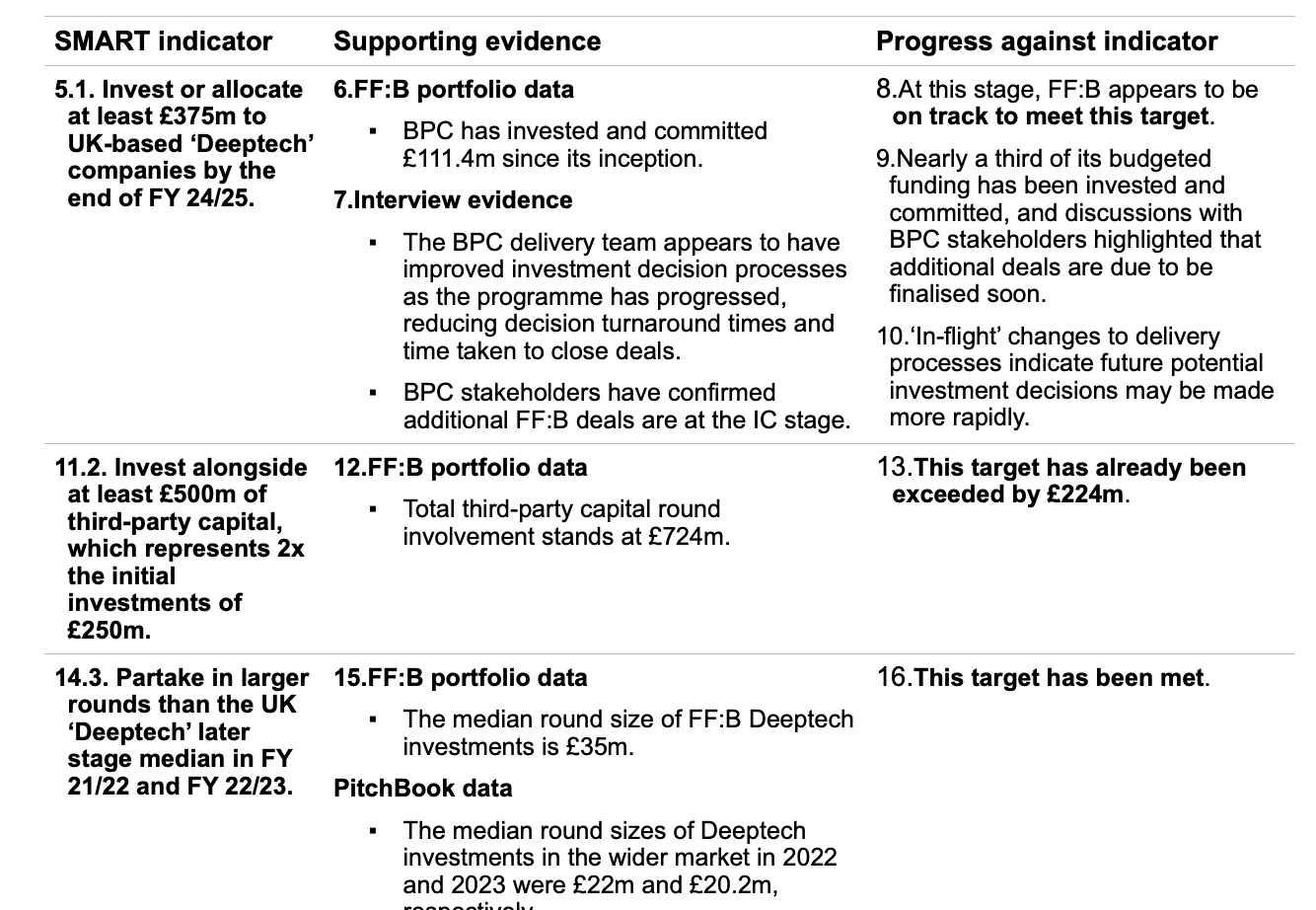

The BBB’s own evaluation of the scheme concluded that it was very successful. But the document is littered with red flags.

Firstly, it uses a series of input measures. The fact that it exceeded its goal of investing alongside £500m could be interpreted as a sign of success or simply a reflection of the glut of private capital on offer at the time. My guess the latter is the case, which does, again, undermine the rationale for the entire programme.

At times, it comes incredibly close to spotting the adverse selection, such as its celebration of essentially bailing out at least one collapsing business.

Considering the volume of private capital available in the UK now, when the government is providing 20% of a company’s Series B funding round, as the BBB celebrates, it’s either a sign that the business is bad or that private investors are being crowded out.

The final cherry on top is the inclusion of a put option, which gives the BBB to ability to cash out if the business becomes insufficiently UK-focused. This is highly unconventional, gives a potentially small investor effective veto rights over corporate decision-making, and seems … political. It also signals that the priority for this work is a narrow conception of ‘UK plc’, rather than real global leadership. The new ECF criteria for investment have also beefed up their UK requirements - a retrograde step.

This only scratches the surface - there are so many funds, and vehicles that it is difficult to keep track and evaluate their performance comprehensively. These include a government UK Innovation Fund (run by external managers) that launched after receiving only £180 million of the planned £1 billion in private commitments and drove good returns after allocating only 40% of its portfolio to UK companies. There’s also a UKRI vehicle that seemingly randomly gave £42 million in non-dilutive grants to a single nanotech company in Northern Ireland, and yet another BBB Managed Funds programme.

When you look at this work in the round - it’s just unclear what it adds up to. It still doesn’t act as an effective small business finance mechanism, while propping up ropey Series B firms doesn’t scream ‘science and tech superpower’.

Reflections

It’s easy to conclude that much of the above is ancient history and that we’re all a lot more sophisticated, now the industry and the ecosystem have evolved. But as the government takes a more interventionist turn, there are a few crucial lessons that extend beyond the venture market.

For a start, we need a significantly better approach to setting goals and evaluating progress. “Closing the equity gap” is a means not an end. Government needs to have clear and consistent reasons for supporting enterprises that are otherwise unable to obtain funding, beyond automatically asserting market failure.

A lack of real objectives leads to policy evaluation by input measurement (“did we spend money?”), which is rarely helpful. Similarly, polling the recipients of said money should not be a measure of success.

Ultimately, we need to clarify the central tension between backing winners versus subsidising the rest. If the real priority is the latter, then we should probably just junk all of this work, channel this money into bulking up the government’s existing SME loan guarantee schemes, and stop paying fees to private managers for the vibes. It might be less ambitious, but it would be significantly cheaper.

If the goal is to back proto, venture-scale winners, there needs to be a transparent way of evaluating whether we’re actually doing this and a policy of cutting off losers.

The public should be able to see returns and the BBB shouldn’t be able to hide behind multiplier figures that consultants they’ve paid have calculated. After a maximum of two funds, ECFs should be able to show signs of success, after which they should be able to raise without the BBB anchoring them. If a start-up isn’t able to raise a Series B, maybe this isn’t evidence of a ‘funding gap’ and instead a sign that they’ve failed.

This also means that the government will have to stop outsourcing policy-making to self-interested market participants. Policymakers often act as if small businesses, universities, and British investors are neutral arbiters on policy questions (unlike evil US tech companies). This is driven by a long-standing and misplaced Westminster awe at people who work in finance, a lack of inhouse expertise, and a wrong-headed belief that small businesses or universities won’t lobby as aggressively for their interests as everyone else.

Finally, we need to avoid the trap of assessing each element individually and losing sight of the macro.

The original rationale for government interventions that now date back 23 years was to crowd in more private capital and to close the ‘equity gap’. The BBB today still talks about crowding in private capital and closing the ‘equity gap’.

Given the passage of time and the money expended so far, it seems reasonable to ask if the problem still does exist and, if so, if the current policy toolkit is the right one.

I’m inclined to argue that the government is operating on outdated assumptions and that it should focus its efforts elsewhere. There’s no shortage of real problems, including poor rates of business investment, low competitiveness levels, bad infrastructure, and terrible government procurement. Fixing these will require more creativity than smashing the subsidy button. Industrial strategy in the UK has historically failed to deviate from this approach. Let’s see if this time really is different.

Disclaimer: These are my views and my views alone. They aren’t those of my employer (Air Street Capital), my friends, my friends’ tennis partners, or my family. I’m not an expert in anything, I get a lot of things wrong, and change my mind. Don’t say you weren’t warned. I’m also not saying that everyone who has received money from the government is bad or undeserving etc. etc. to pre-empt any overly-personal responses.

Photo: a ‘bridge to nowhere’ near Castrop-Rauxel, Germany. (Der Hessi/German Wikipedia)

For a brief (if highly critical account) of this growth, see C Lonsdale, The UK Equity Gap: The Failure of Government Policy Since 1945 (London, 2019) , ch. 4.

Josh Lerner, Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Public Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed - and What to Do About It (Princeton, 2009), pp. 113-4.

Helpfully, the Telegraph have nuked a significant proportion of their archive from the website, so I obtained the text from a third-party service. Happy to provide on request.

I was unable to find a publicly available copy of this report, but I can provide a copy on request that a researcher sent me.

Perhaps the risk is the opposite, that rather than crowding out private funding, BBB is allowing banks to reduce the amount of risk they take with corporate lending, because an other bank will use guarantees such as the Growth Guarantee Scheme. Advisors tell me that the issue is that banks increasingly rely on BBB to underwrite corporate lending moving risk from the private to the public balance sheet (in part).

It would be interesting (or rather not) to compare with other similar schemes across European countries or even more centrally with EIF and EIC money.